We sadly relinquished the Polo in Nelspruit, as outlined in our rental contract, and reverted once again to bus transport. A double-decker Greyhound carried us to Maputo, Mozambique with a slightly frantic border crossing despite already having obtained our visas. One can seemingly infer a lot about a country’s politics and infrastructure by the level of chaos at its borders. The Arrival area at the Mozambique border bore all of the appropriate signage; however, the actual system of queues took on a functional disorder such that, were it not for a few friendly border crossing veterans telling us where to go, we would have been rightly stressed about missing the departing bus on the other side.

We sadly relinquished the Polo in Nelspruit, as outlined in our rental contract, and reverted once again to bus transport. A double-decker Greyhound carried us to Maputo, Mozambique with a slightly frantic border crossing despite already having obtained our visas. One can seemingly infer a lot about a country’s politics and infrastructure by the level of chaos at its borders. The Arrival area at the Mozambique border bore all of the appropriate signage; however, the actual system of queues took on a functional disorder such that, were it not for a few friendly border crossing veterans telling us where to go, we would have been rightly stressed about missing the departing bus on the other side.

We arrived in Maputo and took a cab to a hostel that, according to the cabbie, organized transport to Tofo, a remote coastal town about eight hours north on a pothole-ridden stretch of road. Fatima’s Place was inarguably one of the most filthy, uncomfortable hostels that we have encountered thus far. The attendant was unfriendly, the shared bathrooms atrocious and the rooms musty but we endured it one night for the sake of convenience. At 5:30 the next morning, a shuttle picked us up and carried us, along with seven other backpackers to the chapas station (parking lot). Chapas is the Mozambican version of the mini-bus. As we were among the last to arrive, we were crammed into the back of the bus. There was no luggage storage on the chapas so bags were packed into the aisle, under the seats and in the front of the vehicle, next to the driver. Each row of seats also had a fold-down seat which created an additional seat in the aisle. Think sardines.

We had made a reservation at Bamboozi, which had been recommended by someone we’d met in Coffee Bay. The gray sky was raining down on us in fat, wet drops, which easily penetrated the thatched roof at the reception desk. We carried our packs up a thatch-covered ramp to our chalet – a charming slant-roofed cottage on stilts with patio, private bath and kitchenette. It was oozing character with its walls made of bamboo bundles tied tightly with reeds and ceiling of woven palm fronds covered in thatch. The furnishings were rustic; one look at the dark wood floors, handcrafted kitchen cabinetry and two-burner gas range with antiquated metal tea pot made us smile at the illusion of paradise. The rain continued to pour down while we settled in and we soon realized just how much of an illusion it was.

Water blew through the spaces between the bamboo bundle walls and seeped through the ceiling onto the upper part of the bed, which was soaked through to the mattress. The kitchenette was devoid of pots, pans, cooking utensils, silverware and a refrigerator, though it did have a full set of dishes, a cutting board, a can opener and a spatula. What anyone thought we were going to do with that combination of items still escapes me. We discovered that first evening that we had no hot water and, at least once a day throughout our stay, we would be without either water or electricity. Most of these little inconveniences fall easily into the “This is Africa” category but we also found the staff to be so unfriendly and unaccommodating that we spent the majority of our time and money away from Bamboozi.

Luckily, we found solace at Tofo Scuba, with whom we did our diving. The staff was incredibly friendly and welcoming. They also had a patio restaurant, facing the beach, with the best salads in Africa and, best of all, two tiny Rhodesian ridgeback puppies that tumbled around and tried to chew scuba equipment and everything else in sight. So cute!

Mozambique scuba diving is known for two things: whale sharks and manta rays. After our dive trip to the Red Sea, Aaron had warned me that I would probably be ruined for future dive destinations because my standards would be too high. I didn’t understand what he meant until we dove in Mozambique. We had signed on to dive with Tofo Scuba and planned to do a shallow introductory dive that afternoon, as is usually required when diving with a new shop. As we left the shop to walk around town for a while, one of the dive guys came trailing after us. He said that he’d spoken to his manager and could get us on an earlier deep dive, circumventing the intro dive, if we were interested. Aaron perked up at the suggestion but I was hesitant. It had only been two months since our last dives but it was a new company and unfamiliar equipment. I needed to think it over. Within a half hour, my excitement overtook my reluctance and I acquiesced. We hurried back to Bamboozi to grab our masks and swimsuits and then hurried again to Tofo Scuba for the deep dive.

There were twelve divers on board the pontoon boat as it bounced over the waves and headed out to sea. I was nervous but tried not to show it as Aaron gave me his best reassuring looks. The boat ride to the dive site was about thirty minutes long, plenty of time for my nerves to fray and, when the boat motor cut off at Hogwarts, we quickly slipped into our equipment, which was already assembled. I checked all of my gauges and releases, inflated my buoyancy control device (BCD – inflates or deflates to help you float or sink), and took a couple of breaths from my regulator (tube linking your air tank and your mouth). I heard a funny wheezing sound on the exhale coming through my reg. I was already unnerved by the haste of the dive preparations, the foreign equipment, and the negative buoyancy entry (a first for both Aaron and me). With a negative entry, you enter the water with a fully deflated BCD, head-first down to your depth and collect yourself and your dive buddy at the bottom. It is a more advanced entry than the positively buoyant entry that I am accustomed to where you enter the water with a BCD full of air, which causes you to stay afloat until you calmly collect yourself, then deflate your BCD and descend slowly, feet-first, with your buddy. The negative entry is necessary in water with greater surface current because you don’t want the current to carry you away from your descent point while you’re getting yourself together on the surface.

While the wheeze in my reg added to my tension, I convinced myself that the reg was fine and that I was trained to handle any problems that might possibly arise underwater. Luckily, I didn’t have much time to think about it because the countdown was already in progress for the entry. “Three, two, one…go!” With a hand over my mask and reg, I flipped backwards over the side of the boat and found myself shockingly immersed in a cool sea of tiny white bubbles. I kicked a few times and then held my position, assessing my mental and physical state. The wheeze was still there, with each exhalation, but I was functionally convinced that my panicked breathing pattern was the cause of the noise so, after a few minutes pause, I slowly descended near the anchor line and found my cheeky buddy among the group below.

The day was overcast, following a rainstorm the previous night and the visibility was low. We had been told that manta rays feed on plankton so low visibility was not necessarily a bad thing for the manta seeker. The ocean floor was quite bare of corals and, aside of three different species of starfish, I hardly noticed any underwater life, though I admit that my frenzied mindset skewed my focus. The dive lasted about forty minutes, which included an excruciatingly long safety stop. We ascended without having seen sharks, rays or really anything of interest. As we reached the surface, inflated our BCDs, and waited in the choppy water for the boat to collect us, I said to myself, “I might be done here.” My equipment had worked fine but the whole of the experience was like a bad dream – the kind in which you’re conscious that you’re having a bad dream but still you cannot wake yourself. Once back on the boat, I kept quiet as the boat smacked against the waves on the rough ride back to shore. Anyone who knows me well enough would have seen that I was visibly shaken. Aaron was disappointed in the dive as well and we agreed to take the next day off from diving for sure and then reassess the situation.

The next day was sunny and gorgeous and we began it with a long walk down the beach. As an interesting side note, the guide book warns to be careful about walking along remote stretches of beach because there are still scattered landmines, which are remnants of the decades-long Mozambican civil war. The day was perfect for diving and the fact that I had the itch to hop on a dive boat that morning was reassuring. I felt confident that I’d be able to “get back on the horse” the next day. The beach at Tofo did not disappoint. It is a hotspot for surfers with big, tubular waves and soft sand. In the morning, at low tide, small white clams get washed onto the shore and you can see the clam’s soft, translucent body creep out of its shell and burrow beneath the sand. Young boys walk along the beach, peddling beaded bracelets, shell necklaces, freshly shelled and roasted cashew nuts, and coconut bread. One woman walked along with a baby tied to her back with a sash, carrying a large plastic bin full of mangos on her head. The baby’s head bounced back uncomfortably, unsupported by the sash. We bought some mangos from the woman the second time we saw her and she seemed both kind and desperate in the hot sun.

In the tiny town center, every day was market day. With a couple of guys (Sam and Tyler) whom we had met along the way, we walked to the town center to buy some prawns and a sack of rice to cook dinner. There were several tented stalls with fruit and vegetables and three or four “convenience stores” with packaged items. We bought butter, a bulb of garlic, a coconut, and some candles. We carried everything back to our chalet and borrowed a pot, pan, knife and silverware from the bar. The unfriendly bartender was annoyingly reluctant to lend us any of the requested items, despite the receptionists’ reassurance that we were welcome to use them, but he finally gave them up at Aaron’s insistence. With the tops popped off a round of delicious Mozambican beers (2M, Laurentina and Manica, which are large bottles, usually cheap, cold and easy drinking), we began the preparations for dinner. Aaron took on the nauseating task of cleaning the prawns, removing the exoskeletons and cutting out the “poop chutes”. Sam started the coconut rice with the milk from the coconut and then Tyler cut up the meat of the coconut with his Swiss Army knife so that we could chomp on it as an appetizer. I set the table and created the ambience with music from the laptop and a centerpiece of white taper candles stuck into empty beer bottles. The evening was lovely with great political and religious conversation – our two favorite topics to discuss with foreigners. Dinner was a delicious collaboration and we enjoyed it with coconut bread and bananas.

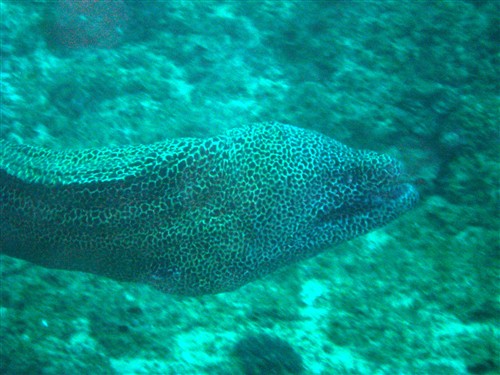

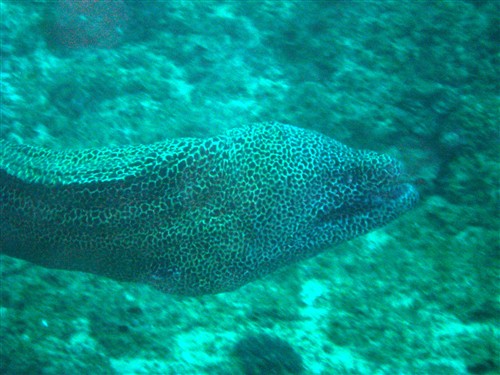

We had scheduled a two tank dive for the next morning and we arrived at the scuba shop refreshed and energized. There were only seven divers this time – a much better number – and as we pushed the pontoon into the water and hopped in over the side, the excitement began to percolate inside us. The first dive site was called Manta Reef and we felt confident about our chances of seeing mantas based on other divers’ reviews of the site. My equipment felt great and the negative entry was smooth. During the two dives combined, we saw five different species of rays, several schools of brightly colored yellow and orange fish and a free-swimming honeycomb moray eel. The visibility was better but still not good…about 8 meters maximum.

We had scheduled a two tank dive for the next morning and we arrived at the scuba shop refreshed and energized. There were only seven divers this time – a much better number – and as we pushed the pontoon into the water and hopped in over the side, the excitement began to percolate inside us. The first dive site was called Manta Reef and we felt confident about our chances of seeing mantas based on other divers’ reviews of the site. My equipment felt great and the negative entry was smooth. During the two dives combined, we saw five different species of rays, several schools of brightly colored yellow and orange fish and a free-swimming honeycomb moray eel. The visibility was better but still not good…about 8 meters maximum.

During the safety stop on the second dive at a site called Sherwood Forest, we spotted about five manta rays gliding through the water below us. Mesmerized by the grace of those beautiful creatures, I began gravitating toward them, unaware of my increasing depth in the murky water with no reference points. And then I felt “the squeeze”. I had learned about the squeeze during my Open Water certification course. It is a pain arising from excess pressure at depth. Before I realized what was happening, a sharp pain shot through my inner right ear. It was an almost mind-numbing pain that shocked me to attention. Suddenly frantic, I looked up, saw the other divers above and realized that I had sunken too low. I ascended slowly while trying desperately to alleviate the pressure in my ear. Nothing seemed to work. The pain didn’t increase but it persisted. One of the dive masters noticed that I was struggling and came over to help but there was nothing he could do. I maintained relative composure and managed to ascend to the surface with the rest of the group, which may or may not have been the best decision but I went slowly and felt okay.

On the surface and throughout the afternoon, my ear continued to throb – a lasting reminder of the importance of following dive protocols and controlling your depth. We returned to the scuba shop and sat down for a couple of their killer salads while reveling in the success of our ray spottings. My ear did eventually did find its happy place again but we were finished diving nonetheless. Despite religious application of sun block, both of our faces got sunburned such that we had to hide beneath the brims of our hats for the last sunny day in Tofo. Our chalet was without power for most of the day so we wandered around the beach and found other places to relax. The waves looked so intense and inviting but the threat of more sun exposure on our already rosy mugs kept us ashore.

That night, as we packed our things once again in preparation for the four a.m. bus ride back to Maputo, we both agreed that we were not sad to be leaving. We had come for the diving and, even though we didn’t see any whale sharks, the manta sightings were fantastic. The beach was beautiful and the town had a feeling of quiet serenity. The discomfort of our accommodation, in conjunction with weather that was either pouring rain or oppressively hot and humid, kept us from truly relaxing. I honestly believe that our experience would have been better at a different resort but that’s the breaks on the road. Sometimes it’s good and sometimes it’s bad. Sometimes it’s preferable to endure a bad place for a few extra nights than to pack it all up again in an attempt to upgrade. It really depends on your mood.

I couldn’t, in good conscience, end this entry without touching upon the border crossing from Mozambique to South Africa. We took a Greyhound bus from Maputo to Johannesburg. The bus arrived at the border and all of the passengers disembarked and walked to the Departure area on the Mozambican side. Being Saturday morning, a long line had formed, spilling outside the door and into the already hot morning sun. As we waited in the queue, sweating along with the other civilized people, a group of tourists cut into the section of the line that was just inside the door while no one up there did anything to stop them. Aaron yelled from the back of the line but with minimal effect. We stood, annoyed, while people pushed, shoved and cut into line without a second thought. Once inside, we found ourselves literally sandwiched between sweaty Africans as we defensively held our position through the resurrection of some of our old basketball skills (pivoting, boxing out…and a little elbow action when necessary). After about an hour, we reached the front of the line and, with the exit stamps still gleaming on our passports, left Mozambique, probably never to return.

With a sigh of relief, we walked quickly to the Arrivals area on the South African side. We arrived to find a beautiful single-file line that stretched around the building, almost all the way to the Departure area on the opposite side. The line moved slowly but we eventually reached the inside of the building, which was packed with more sweaty people (and when I say sweaty, keep in mind that most Africans do not wear deodorant), kept in queue by a series of guardrails. At first glance, it seemed like a reasonably efficient system until we realized why the line had been moving so painfully slowly. Of the six windows, four were occupied by working agents and two were empty. One window was reserved for “Diplomats” of whom there were none. The Diplomat window attendant, rather than taking the next person in the official queue, seemed to take selected persons who managed to circumvent the inside part of the queue. Meanwhile, on the opposite end, a shortcut had been discovered wherein a separate small but consistent line had formed by people who had sneaked over from the Departure side; these people were being served without having waited in the queue at all! The attendant at that far window saw what was happening but did little to stop it. All that it would take to remedy the situation at the borders is a couple of stern-looking guards with night sticks keeping order in the queue. It took us a total of two infuriating hours to cross the border and continue on our journey.

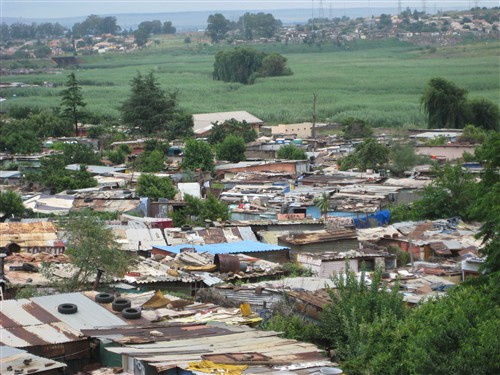

Situations like the above-mentioned border crossing make me want to throw my hands in the air and scream, “Why? Why? Why? Why is it so difficult to be civilized?” After more than three months in Africa, I am no closer to finding the answer to that question and I find it maddening! For all of its appealing wild beauty and colorful culture, sometimes Africa can feel like an incorrigible child. It takes patience and determination to endure the many discomforts involved in African travel, particularly in a place like Mozambique where years of civil war have dramatically damaged the infrastructure. If you can look beyond the blemishes and peel back the rough exterior, you will find a sensational raw beauty and vulnerability that touches your soul and forever changes your life for having witnessed it. In hindsight, you’ll always find that it was worth it.

We left Johannesburg on the evening of December 18 and, after thirty-one hours and three connections, we arrived in Boston sleep deprived (neither of us can sleep on planes) but otherwise unscathed. As we arrived on American soil, I began to softly sing every patriotic song that I could think of. Mark picked us up and drove us to Providence where we met up with more of the Rooney clan. We all caught up over a quick drink in the hotel bar before they headed off to the Mulhearns’ for dinner and we passed out for a good twelve hours. When we finally re-surfaced, the pre-wedding festivities were already brewing as more friends and family began to arrive.

We left Johannesburg on the evening of December 18 and, after thirty-one hours and three connections, we arrived in Boston sleep deprived (neither of us can sleep on planes) but otherwise unscathed. As we arrived on American soil, I began to softly sing every patriotic song that I could think of. Mark picked us up and drove us to Providence where we met up with more of the Rooney clan. We all caught up over a quick drink in the hotel bar before they headed off to the Mulhearns’ for dinner and we passed out for a good twelve hours. When we finally re-surfaced, the pre-wedding festivities were already brewing as more friends and family began to arrive.

Lena stole the show for the entire week. My family is as crazy about her as we are and she went from one lap to another, received a minimum of a hundred kisses each day, and was the main topic of conversation. When we finally left, it was a toss up as to who they were more sad to say goodbye to, us or Lena. We loved every minute of being home for the holidays but it was hard to say goodbye. We would love to have our family and friends meet us somewhere along the way but we understand that, while we’re busy squandering our fortune, most other people’s lives are continuing on as usual. It will be initially hard to return to the hostel world after basking in the comforts of home for two wonderful weeks (I’m already bracing myself for the squat toilets in India) but whatever adventures and challenges the next fourteen months bring will be met with open minds and open hearts. On New Year’s eve, we are off to India with big dreams. The world is beautiful and, with a new year ahead full of promise, we feel blessed for this opportunity to see it.

Lena stole the show for the entire week. My family is as crazy about her as we are and she went from one lap to another, received a minimum of a hundred kisses each day, and was the main topic of conversation. When we finally left, it was a toss up as to who they were more sad to say goodbye to, us or Lena. We loved every minute of being home for the holidays but it was hard to say goodbye. We would love to have our family and friends meet us somewhere along the way but we understand that, while we’re busy squandering our fortune, most other people’s lives are continuing on as usual. It will be initially hard to return to the hostel world after basking in the comforts of home for two wonderful weeks (I’m already bracing myself for the squat toilets in India) but whatever adventures and challenges the next fourteen months bring will be met with open minds and open hearts. On New Year’s eve, we are off to India with big dreams. The world is beautiful and, with a new year ahead full of promise, we feel blessed for this opportunity to see it.

We sadly relinquished the Polo in Nelspruit, as outlined in our rental contract, and reverted once again to bus transport. A double-decker Greyhound carried us to Maputo, Mozambique with a slightly frantic border crossing despite already having obtained our visas. One can seemingly infer a lot about a country’s politics and infrastructure by the level of chaos at its borders. The Arrival area at the Mozambique border bore all of the appropriate signage; however, the actual system of queues took on a functional disorder such that, were it not for a few friendly border crossing veterans telling us where to go, we would have been rightly stressed about missing the departing bus on the other side.

We sadly relinquished the Polo in Nelspruit, as outlined in our rental contract, and reverted once again to bus transport. A double-decker Greyhound carried us to Maputo, Mozambique with a slightly frantic border crossing despite already having obtained our visas. One can seemingly infer a lot about a country’s politics and infrastructure by the level of chaos at its borders. The Arrival area at the Mozambique border bore all of the appropriate signage; however, the actual system of queues took on a functional disorder such that, were it not for a few friendly border crossing veterans telling us where to go, we would have been rightly stressed about missing the departing bus on the other side. We had scheduled a two tank dive for the next morning and we arrived at the scuba shop refreshed and energized. There were only seven divers this time – a much better number – and as we pushed the pontoon into the water and hopped in over the side, the excitement began to percolate inside us. The first dive site was called Manta Reef and we felt confident about our chances of seeing mantas based on other divers’ reviews of the site. My equipment felt great and the negative entry was smooth. During the two dives combined, we saw five different species of rays, several schools of brightly colored yellow and orange fish and a free-swimming honeycomb moray eel. The visibility was better but still not good…about 8 meters maximum.

We had scheduled a two tank dive for the next morning and we arrived at the scuba shop refreshed and energized. There were only seven divers this time – a much better number – and as we pushed the pontoon into the water and hopped in over the side, the excitement began to percolate inside us. The first dive site was called Manta Reef and we felt confident about our chances of seeing mantas based on other divers’ reviews of the site. My equipment felt great and the negative entry was smooth. During the two dives combined, we saw five different species of rays, several schools of brightly colored yellow and orange fish and a free-swimming honeycomb moray eel. The visibility was better but still not good…about 8 meters maximum.