Preface: This story ends sadly in later detail. It would normally be a private matter but the stories surrounding our experience simply must be told.

The tale of my emergency visit to a Chinese hospital begins with the funny story of how we found out that I was pregnant. I knew it in my heart on the date of conception. I knew it so surely that I immediately swore off caffeine and alcohol and began taking prenatal vitamins. When the time came to take a pregnancy test, we were in Xi’an. Sometime between the Terracotta Warriors and the Giant Pandas, we managed to find a Walmart and picked up two tests. Although the instructions were in Chinese, I felt confident in my ability to interpret the results. However, this proved not to be the case. Rather than two possible results, the instructions showed six possible results. Neither Aaron nor I could conclude anything more definitive than “maybe”. Aaron suggested asking the girls on the hostel staff to translate but I wasn’t ready to bring strangers into our private situation. We decided to save the other test and try again at the next opportunity, which turned out to be in Shanghai almost a week later. Aaron picked up two different kinds of tests and asked the hostel staff in Shanghai to translate. Between those and the one left over from Xi’an, we had three undeniably positive pregnancy tests.

We were over the moon. Suddenly our entire focus switched from trip plans to babies…to when and how to share the news of our blessing. We immediately scoured the internet to research the safety of traveling while pregnant and made an appointment for a first pregnancy exam with a UK-trained OB-GYN at a travel medical clinic in Kathmandu.

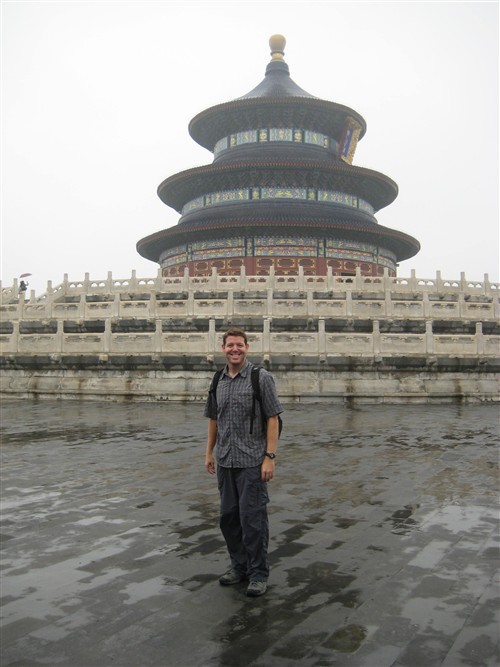

During our last days in China, I stayed in and rested a lot. We took the overnight train from Shanghai to Beijing. We had a room booked there for one night and then an early flight to Kathmandu the following morning.

Around 5:00 on the evening of our arrival in Beijing, Aaron had just returned from a day of solo sightseeing; I had been lying around all day with the guiltlessness of a self-indulgent Mother Hen. We were discussing the news that Tibet had just reopened to foreigners when I felt a sudden horrible pain shoot from my abdomen down through my cervix. The first shot scared me more than anything but, within two seconds, I was writhing on the bed in agonizing pain. It was excruciating and relentless, literally paralyzing my mid-section.

Aaron sat on the chair in shock and fear, not knowing what to do but knowing that something was terribly wrong. After a minute of debate on whether to call for an ambulance, I acquiesced. Aaron disappeared into the hallway to get help and soon returned with three people from the hostel staff, including one man who claimed to be a doctor. He felt my forehead – my temperature had skyrocketed almost instantly and I had broken out in a cold sweat – and saw the agony on my face. He told us what we already knew…that I needed to go to the emergency room.

A girl from the hostel informed us that the hospital refused to send an ambulance due to the short distance but a taxi was on the way. Great. The taxi arrived less than ten excruciating minutes later and Aaron carried me outside. The girl, named Judy, from the hostel said that she would accompany us and we would soon discover how crucial her presence would be.

At the hospital emergency entrance, Aaron carried me inside – the pain had subsided somewhat in the car – and we were directed to a large room with two beds. The other bed was occupied by a snowy-haired Chinese woman who was moments away from death’s door, her saddened adult children huddled around her.

Several minutes passed where nothing happened. Finally, Aaron was called upon to fill out paperwork (with Judy’s help) and two nurses arrived with a saline drip. As they came at me with the needle, because I didn’t actually see them remove it from its sterile wrapping, the thought crossed my mind to ask them to wait until Aaron returned but I was complacent or intimidated by the language barrier, maybe a little of both.

When Aaron returned, he said that the desk clerk was trying to get him to pay cash in advance for each individual task performed, starting with the paperwork filing fee. They wouldn’t take his credit card and since it was our last night in China, we were down to our last notes of local currency. Finally, in lieu of running to the ATM every half hour, he convinced them to hold his passport as collateral until the end.

A nurse joined us and began hooking me up to a machine that looked like something out of an Austin Powers film or an old Star Trek episode with large metal suction cups attached to a series of brightly-colored tubes. The cynic in me was bubbling to the surface as Aaron and I exchanged knowing glances. Soon, Judy returned with the news that we needed to go to another floor for an ultrasound. She and Aaron, along with a single nurse, wheeled my bed to the ultrasound lab. The lights in the empty hallway were off, which seemed eerie for a hospital, but we later discovered that they were motion sensitive. My bed was wheeled next to the ultrasound machine. The technician squirted the jelly onto my belly, positioned the wand near my navel, and then abruptly stopped. Her explanation was in Chinese, of course, and it took nearly twenty minutes of discussion in the hallway to help us understand that the tech wanted me to have a full bladder. She wanted me to go all the way back to my room with the dying woman and come back in half an hour. It seemed ridiculous but what else could we do? I started chugging water.

While we waited for the liquids to swell my bladder, I was wheeled (by only Aaron and Judy this time) to another floor to see a doctor. A middle-aged male doctor, surrounded by a swarm of curious nurses, asked me a few questions about the pain and pressed on my stomach in several places before quickly concluding that it was probably just something I ate. No ultrasound, no bloodwork…it must have been the two pieces of fruit that did it! Are you kidding me? Upon hearing his diagnosis, I wanted to scream from the rooftops about this physician’s total incompetence and, of course, throw in a few “I hate Chinas” for good measure. Instead, I kept my composure and calmly explained, while Judy translated, that we had over 36 hours of international travel scheduled to begin the next morning so, if it wouldn’t be too much trouble, I’d like to have an ultrasound and some bloodwork to determine that my baby is okay and whether it is safe for me to travel. The pompous ass seemed a bit put off that I didn’t accept his conclusion outright. After proactively managing my own hospital visit, I finally got my tests.

The ultrasound took a long time and the tech refused to give any explanations, although it was not hard to tell that something was wrong. For the blood test, Aaron and Judy wheeled my bed up to a window where I stuck my hand under the glass and a technician pricked my finger. The transaction was impersonal and we never did receive the results of the tests or learn what tests they ran.

We were baffled by the lack of orderlies in this place and the bizarre passivity of the staff. We wheeled ourselves around and essentially ordered our own tests; there didn’t seem to be a single doctor in charge of my case. Aaron had determined from the number of military personnel wandering the halls that this was a military hospital and Judy confirmed it. No one spoke English, not even the doctors, which led me to conclude that they were trained in China which in turn filled me with a natural distrust in their abilities; not because they were Chinese but because they were not trained in a Western country. This is perhaps unfairly discriminating but my experience so far had supported that notion and, when you’re in an emergency room in a developing nation, where no one can communicate with you, you cannot help but let a few crazy thoughts into your mind. Mine was swimming with paranoid possibilities.

Back in my room, Aaron and Judy left to pursue the next stage of my treatment and I was left with the dying woman and her family. The scene reminded me of the day my grandmother passed away with her three daughters and one granddaughter (me) around her bedside. Seeing the Chinese family grieve and pray in the same way made me feel a bond of human suffering. We kept glancing at each other and then shyly looking away. I wanted to comfort them but I didn’t know how.

Aaron and Judy returned soon followed by a general surgeon. He had been much too busy to see me but Aaron and Judy persistently stalked him until he became available. The squeaky wheel gets the grease, as Aaron likes to say. This doctor pressed around my mid-section, apparently to rule out Appendicitis, and then disappeared as quickly as he came.

I was alone once again. Aaron and Judy had gone to the front desk, the staff had dissipated, and my bladder felt like an over-filled water balloon. In our earlier haste at the hostel, we had forgotten my shoes. I flagged down a passing orderly and attempted to mime my need for some slippers but she just shook her head confusedly as if it was a crazy notion that a hospital would have slippers for its patients. Well, there was no way in hell that I was going barefoot.

Minutes later, Aaron returned and lent me his size elevens to make the trip to the restroom. I fished my roll of toilet paper out of the backpack and shuffled slowly down the hall. What I found there was appalling. There were three filthy, germ-infested stalls: two squat toilets and one Western. The Western stall was cluttered with miscellaneous debris as if it doubled as a janitorial closet. The lights were dim but I could see that the toilet seat was soaked with droplets of liquid. I gasped in disgust. It’s all part of the Twilight Zone nightmare, I told myself. Just do your thing, don’t touch ANYTHING, and get the hell out of here! There was no toilet paper or soap in the restroom and I was glad to have brought my own. I know…I should be at a point in my life where Third World restrooms cannot shock me anymore but this was in a hospital!

After some more waiting, a woman claiming to be the OB-GYN reported that my baby was not attaching properly and there was a chance that I would lose it. She said that she could give me a shot that would help my chances. She prescribed Progesterone and a week of bedrest. Bedrest…in China! Now, in case you haven’t followed our China travels, I should explain that we had already stayed about a week too long. A week of bedrest in China would be torture for both of us! And even then, the odds weren’t good.

Aaron settled the hospital bill, which came to the equivalent of US$60. The hostel had sent their car and driver to pick us up. It was 9pm. We settled back into our room and ordered dinner from the café. We did some quick research online about miscarriage and the efficacy of bedrest. Almost every source agreed that there is no conclusive evidence that bedrest helps to prevent miscarriage, although many physicians still prescribe it.

While Aaron was getting dinner, I had some time alone to think. I thought about the emotional and financial effects of spending another week in China; about the intense travel schedule – four flights and a twelve hour layover in Bangkok – that lay between Beijing and Kathmandu; about the possibility of a medical emergency in flight; and about our scheduled appointment with the Western-trained (and likely English-speaking) OB-GYN in Kathmandu. When Aaron returned, I told him that the best thing for our family was to get out of China. He hesitated but, in the end, he didn’t object because he knew that I was right. The first leg of our itinerary departed at 10:00 the next morning and, with our hearts full of prayers, we were on it.

I was in the frame of mind to lay low in Pokhara and do everything possible to stay relaxed and prevent any further emergency room visits. As Aaron was feeling physically fine and needed some good distractions, we signed him up for a few adventure activities, the first of which was paragliding. I rode along for that one (in the truck, not the chute) and watched him leap from the top of the mountain and glide through the air over the breathtaking Pokhara Valley. I knew he was okay shortly after take off when I heard an ecstatic “Woohoo!” echo through the valley to which I replied, “You’re flyiiiiiing!” I excitedly snapped a dozen pictures of my falcon-like husband. As the driver and I made our way back down the mountain, we stopped to pick up an amazing sixteen locals, mostly women and children, to carry them down to town. I saw one woman pass him a bill but most paid nothing. There is just an unwritten rule that, if you have an empty truck and people need a ride, you stop for them. Though the extra stops prevented me from reaching the landing point in time for the landing, I was very moved by this beautiful yet commonplace Third World gesture.

I was in the frame of mind to lay low in Pokhara and do everything possible to stay relaxed and prevent any further emergency room visits. As Aaron was feeling physically fine and needed some good distractions, we signed him up for a few adventure activities, the first of which was paragliding. I rode along for that one (in the truck, not the chute) and watched him leap from the top of the mountain and glide through the air over the breathtaking Pokhara Valley. I knew he was okay shortly after take off when I heard an ecstatic “Woohoo!” echo through the valley to which I replied, “You’re flyiiiiiing!” I excitedly snapped a dozen pictures of my falcon-like husband. As the driver and I made our way back down the mountain, we stopped to pick up an amazing sixteen locals, mostly women and children, to carry them down to town. I saw one woman pass him a bill but most paid nothing. There is just an unwritten rule that, if you have an empty truck and people need a ride, you stop for them. Though the extra stops prevented me from reaching the landing point in time for the landing, I was very moved by this beautiful yet commonplace Third World gesture.

Next, we visited Durbar Square in the older part of town. Once the site of royal coronations, the square has more temples and shrines per square meter than anywhere we’ve been. Most of the buildings date back to the 17th and 18th centuries and little has been done to preserve or restore them. What I found most interesting about the religious structures in Durbar Square was how casually they were treated. People climbed all over them, lazing the day away on the upper levels and watching the world go by.

Next, we visited Durbar Square in the older part of town. Once the site of royal coronations, the square has more temples and shrines per square meter than anywhere we’ve been. Most of the buildings date back to the 17th and 18th centuries and little has been done to preserve or restore them. What I found most interesting about the religious structures in Durbar Square was how casually they were treated. People climbed all over them, lazing the day away on the upper levels and watching the world go by. Our last several days in China were a blur. We checked back into our Shanghai hostel for one last night and, on the recommendation of some fellow travelers, we went to see a Chinese Acrobatics show. We arrived early and watched the small theatre fill up as foreigners in enormous tour groups filed in behind their dutiful guides. The show began with a group of high-energy gymnasts bounding across the stage and soaring through narrow hoops, barely dodging one another in precisely choreographed stunts. Another performer was a young girl, who mounted a small elevated platform in handstand position, and did a ten-minute routine supporting her body weight with only one arm. The men and women were equally impressive; the men with their strength and agility, the women with their grace and poise while lifting and maintaining enormous heavy loads. The show was spectacular and we were mesmerized for ninety minutes by the talented performers.

Our last several days in China were a blur. We checked back into our Shanghai hostel for one last night and, on the recommendation of some fellow travelers, we went to see a Chinese Acrobatics show. We arrived early and watched the small theatre fill up as foreigners in enormous tour groups filed in behind their dutiful guides. The show began with a group of high-energy gymnasts bounding across the stage and soaring through narrow hoops, barely dodging one another in precisely choreographed stunts. Another performer was a young girl, who mounted a small elevated platform in handstand position, and did a ten-minute routine supporting her body weight with only one arm. The men and women were equally impressive; the men with their strength and agility, the women with their grace and poise while lifting and maintaining enormous heavy loads. The show was spectacular and we were mesmerized for ninety minutes by the talented performers. The Yonghe Temple, or Palace of Peace and Harmony Lama Temple, is most commonly referred to simply as the “Lama Temple”. The Lama Temple is a Tibetan Buddhist temple and monastery, one of the largest of its kind in the world. The expansive grounds contained five main halls separated by courtyards, and numerous other unimpressive buildings. I stumbled upon a religious ceremony at its conclusion and was fascinated by the costumes of the presiding monks. Their orange robes were standard issue, but they each wore large, yellow hats resembling the comb on a rooster’s head – a very entertaining sight indeed. The highlight of my self-guided tour was a 26-meter tall, gold-covered statue of the Maitreya Buddha carved from a single piece of White Sandalwood and housed in one of the pavilions – it was truly impressive. After my brief visit, I left the temple complex unimpressed and boarded the metro to return home to my wife…and ready to leave China.

The Yonghe Temple, or Palace of Peace and Harmony Lama Temple, is most commonly referred to simply as the “Lama Temple”. The Lama Temple is a Tibetan Buddhist temple and monastery, one of the largest of its kind in the world. The expansive grounds contained five main halls separated by courtyards, and numerous other unimpressive buildings. I stumbled upon a religious ceremony at its conclusion and was fascinated by the costumes of the presiding monks. Their orange robes were standard issue, but they each wore large, yellow hats resembling the comb on a rooster’s head – a very entertaining sight indeed. The highlight of my self-guided tour was a 26-meter tall, gold-covered statue of the Maitreya Buddha carved from a single piece of White Sandalwood and housed in one of the pavilions – it was truly impressive. After my brief visit, I left the temple complex unimpressed and boarded the metro to return home to my wife…and ready to leave China.