Posted under China

In Xi’an we have experienced personally the effects of gross overpopulation in China. We came to Xi’an – on the night train from Beijing – to see the famous Terracotta Warriors, proclaimed by some to be the Eighth Wonder of the World. Xi’an is what you might call a budding metropolis – another bastion of consumerism with what appears to the outsider as a healthy middle class. The city is consumed by concrete – impersonal residential towers and enormous commercial buildings. It is not a typical American downtown with rings of suburbs but rather an ever-expanding city almost perpetually cloaked in haze.

Our hostel offered a guided trip to see the Terracotta Warriors but I convinced Aaron that their premium was too high and we should take the city bus instead. A member of the hostel staff told us which buses to take: the 603 to the train station; then switch to the 306. It sounded easy enough. We walked to the bus stop and waited for the 603. We had seen many city buses, in Beijing and Xi’an, pass by with bodies stuffed in like sardines so we should not have been surprised when the double-decker 603 came to a halt at our stop disguised as a sardine tin.

Only three passengers disembarked and, at the same time, three Chinese girls slipped in front of us to the entry door. This is common practice in China. There is no etiquette, no chivalry here. It’s every man for himself. And if you’re standing in a line, a person will cut in front of you while looking you right in the eye. Luckily, we’ve had prior experience with this uncivilized behavior and are unabashed about throwing an elbow or shoulder in front of these devious little cutters. In the case of the three Chinese girls at the bus stop, we let them go for two reasons: 1) from their usurped position directly in front of us, their removal would have required an unusual amount of manhandling, which surely would have caused a scene; and 2) with the size and disorganization of the crowd at the bus stop, we were not 100% certain that we’d arrived before them.

So the three girls climbed onto the packed bus and we followed. Not surprisingly, three more people pushed their way on behind us with one vocal and pushy woman imploring us to push further into the shoulder-to-shoulder crowd. To complicate matters, the bus was designed for Chinese people so Aaron was about eight inches too tall; he could not stand straight but had to hunch over in the claustrophobic cabin. Thankfully, after a few stops, he found a reprieve by standing in the stairwell leading to the upper deck. After about thirty long minutes, we finally reached the train station and easily found the 306, which was much more spacious and comfortable, for the remaining hour ride to the Warriors.

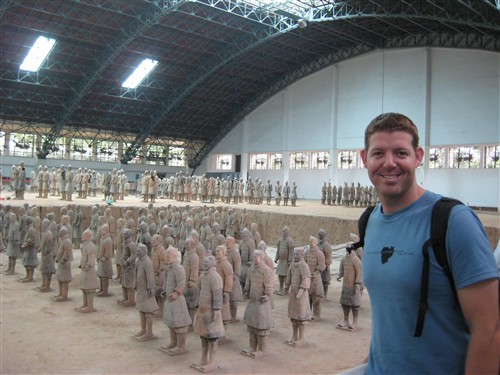

Discovered by accident in 1974 by peasants digging a well, the Army of Terracotta Warriors is one of most important discoveries of ancient Chinese history. Commissioned by Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of China, the army of thousands of life-size soldiers in battle formation stands guard at the emperor’s tomb. Some say Qin Shi Huang feared evil spirits in the afterlife while others believe that he expected his rule to continue after death. Ancient scholars seem to agree that the emperor was paranoid and fanatical, which would explain his obsession with creating a “pretend” army. Whatever the case, the army of soldiers, when viewed in its partially restored state, is undeniably impressive.

Discovered by accident in 1974 by peasants digging a well, the Army of Terracotta Warriors is one of most important discoveries of ancient Chinese history. Commissioned by Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of China, the army of thousands of life-size soldiers in battle formation stands guard at the emperor’s tomb. Some say Qin Shi Huang feared evil spirits in the afterlife while others believe that he expected his rule to continue after death. Ancient scholars seem to agree that the emperor was paranoid and fanatical, which would explain his obsession with creating a “pretend” army. Whatever the case, the army of soldiers, when viewed in its partially restored state, is undeniably impressive.

The museum is constructed over the three original excavation sites. It is recommended to view the pits in reverse order so we began with Pit 3 – the smallest – and worked our way to Pit 1 – the largest and most impressive. The soldiers were positioned in long corridors divided by walls made of rammed earth and wood beams. The most fascinating aspect of the army was the level of unique detail among the statues. Each soldier had a unique face. Even the tread on the shoes was not uniform. The soldiers’ dress and hairstyles differentiated their rank and all held bronze weapons, though the weapons had been removed.

The excavation sites each showed the broken condition in which the soldiers were discovered. A sign near one of the pits indicated that, to date, not a single statue has been unearthed intact. When we reached Pit 1, where approximately 6,000 soldiers are thought to stand (although only 2,000 have been restored to date), we met with the postcard view of the Terracotta Army. The excavation site was larger than a regulation football field and less than half of the site had been fully excavated; the two-thousand restored warriors, dating back to 210 B.C., stood stoically in battle formation with horses and all. As we stood facing the front line, it was easy to imagine the army in its full grandeur and completion with Emperor Qin Shi Huang pacing back and forth, barking orders at his earthen men.

The excavation sites each showed the broken condition in which the soldiers were discovered. A sign near one of the pits indicated that, to date, not a single statue has been unearthed intact. When we reached Pit 1, where approximately 6,000 soldiers are thought to stand (although only 2,000 have been restored to date), we met with the postcard view of the Terracotta Army. The excavation site was larger than a regulation football field and less than half of the site had been fully excavated; the two-thousand restored warriors, dating back to 210 B.C., stood stoically in battle formation with horses and all. As we stood facing the front line, it was easy to imagine the army in its full grandeur and completion with Emperor Qin Shi Huang pacing back and forth, barking orders at his earthen men.

We completed our visit with a brief stop in the museum of artifacts, which showcased some of the weaponry and tools found near the sites as well as two half-size bronze chariots with drivers, remarkable in their level of detail. As we followed the exit signs to the parking lot, we were steered through a “village” of souvenir stalls. Strangely, the single alley of stalls was surrounded by a, two-storey commercial structure, seemingly intended for tourist amenities, which lay almost completely vacant. Aaron suggested that it might be an initiative of the Chinese government to create construction jobs, even though there is no practical need for the completed projects, though we were never able to confirm it. We rode the 306 bus back to the train station in Xi’an but decided to walk back to the hostel rather than enduring the claustrophobic misery of the 603.

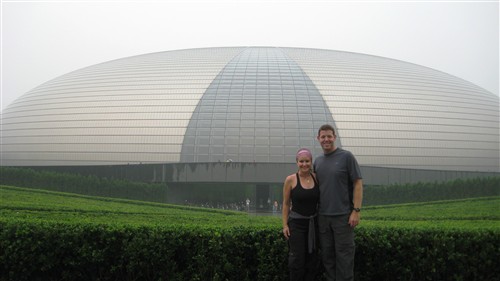

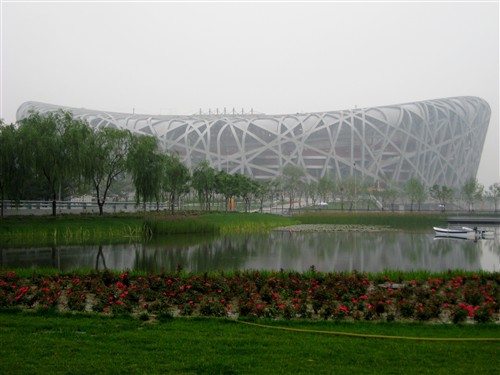

The Beijing National Stadium, a.k.a. the Bird’s Nest for its architecture, will be the site of the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2008 Summer Olympic Games as well as the main track and field events. The area around the Bird’s Nest was fenced off so we could not get very close to it. We had the driver stop for a few minutes along the side of the road so that we could join the other gawkers. The building was a massive display of modern architecture, in which soaring curvature has replaced the maximum functionality of space as the primary initiative of the endeavor. The gargantuan steel structure invokes shock and awe in the beholder rather than admiration of beauty in the traditional sense. It is inarguably an impressive artistic and architectural feat.

The Beijing National Stadium, a.k.a. the Bird’s Nest for its architecture, will be the site of the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2008 Summer Olympic Games as well as the main track and field events. The area around the Bird’s Nest was fenced off so we could not get very close to it. We had the driver stop for a few minutes along the side of the road so that we could join the other gawkers. The building was a massive display of modern architecture, in which soaring curvature has replaced the maximum functionality of space as the primary initiative of the endeavor. The gargantuan steel structure invokes shock and awe in the beholder rather than admiration of beauty in the traditional sense. It is inarguably an impressive artistic and architectural feat.

Our duck arrived after about thirty minutes and the chef began carving it up. Due to my little carcass phobia, I kept my eyes on Aaron and prayed that nothing that arrived at the table would resemble a living animal or its internal organs. We were served a few slivers of flavorful skins first, which we happily doused in plum sauce. Next, the sliced meat was presented in an expertly carved pile. Thankfully, the carcass was then taken away. The waitress demonstrated the traditional assembly for Peking duck by dipping two pieces of meat into the plum sauce and placing them in the center of one of the rice pancakes. She then added a sliver of spring onion and a julienne cucumber and folded the pancake neatly around the filling, using my chopsticks. Dinner was delicious! We finished just in time to race back to the hostel, collect our bags, and head to the train station.

Our duck arrived after about thirty minutes and the chef began carving it up. Due to my little carcass phobia, I kept my eyes on Aaron and prayed that nothing that arrived at the table would resemble a living animal or its internal organs. We were served a few slivers of flavorful skins first, which we happily doused in plum sauce. Next, the sliced meat was presented in an expertly carved pile. Thankfully, the carcass was then taken away. The waitress demonstrated the traditional assembly for Peking duck by dipping two pieces of meat into the plum sauce and placing them in the center of one of the rice pancakes. She then added a sliver of spring onion and a julienne cucumber and folded the pancake neatly around the filling, using my chopsticks. Dinner was delicious! We finished just in time to race back to the hostel, collect our bags, and head to the train station.

The architectural design of the entrance to the Summer Palace was strikingly similar to that of the Forbidden City – a pagoda-like structure ornamented with the same ornate patterns of red, gold, green and blue. Once inside, we wove our way through the throngs of tour groups – each group with its own matching hats – in the courtyard. We emerged at the edge of the sparkling blue Lake Kunming, which occupies three-quarters of the palatial grounds. A bluish-purple haze – likely a combination of clouds and smog – cast a mystical glow across the glassy surface of the lake and obscured the “templescape” on the northern shore. An elaborately decorated ferry cut through the glass as it carried visitors back and forth across the lake while paddleboats and rowboats careened about on the breezeless day.

The architectural design of the entrance to the Summer Palace was strikingly similar to that of the Forbidden City – a pagoda-like structure ornamented with the same ornate patterns of red, gold, green and blue. Once inside, we wove our way through the throngs of tour groups – each group with its own matching hats – in the courtyard. We emerged at the edge of the sparkling blue Lake Kunming, which occupies three-quarters of the palatial grounds. A bluish-purple haze – likely a combination of clouds and smog – cast a mystical glow across the glassy surface of the lake and obscured the “templescape” on the northern shore. An elaborately decorated ferry cut through the glass as it carried visitors back and forth across the lake while paddleboats and rowboats careened about on the breezeless day. Past the dancers, we came upon my favorite area of the Summer Palace – Suzhou Street. Crossing an arched stone bridge, we caught our first glimpse of the traditional, red-laced shopfronts edging around a narrow canal. Suzhou Street was created as a replica of Jiangsu, a famous Chinese canal town. Its charming shopfronts were fully functional with tea houses, souvenir shops, Chinese calligraphers, painters, and photography studios in which visitors could dress in traditional Chinese silk costumes. A lone flute-seller demonstrated his instrument on the walkway, filling the entire canal town with his eerie, tranquil notes. We took a single leisurely lap around the riverside walkway and were beckoned inside every shop, gallery and tea house that we passed, which detracted only slightly from the charm of the experience.

Past the dancers, we came upon my favorite area of the Summer Palace – Suzhou Street. Crossing an arched stone bridge, we caught our first glimpse of the traditional, red-laced shopfronts edging around a narrow canal. Suzhou Street was created as a replica of Jiangsu, a famous Chinese canal town. Its charming shopfronts were fully functional with tea houses, souvenir shops, Chinese calligraphers, painters, and photography studios in which visitors could dress in traditional Chinese silk costumes. A lone flute-seller demonstrated his instrument on the walkway, filling the entire canal town with his eerie, tranquil notes. We took a single leisurely lap around the riverside walkway and were beckoned inside every shop, gallery and tea house that we passed, which detracted only slightly from the charm of the experience.

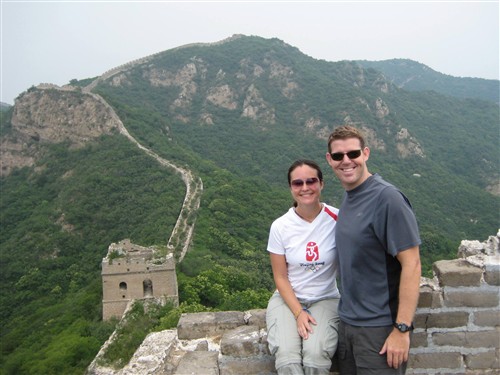

Our Chinese guide was a little old man (perhaps sixty, though it is always hard to tell with Asians because they age so well) who spoke only one word of English: “okay”. We never caught his name; he was introduced simply as “the guide” when we picked him up on the side of the road. From now on, I’ll refer to him as Wang because he needs a name. Wang led our group in slow, measured steps up the mountainside, on a narrow, rocky trail encroached upon by thick brush from both sides. The slow but steady pace of the ascent made the otherwise rigorous terrain quite manageable, even for a little whiner like me who hates steep inclines. Wang clearly felt no sense of urgency and everyone in the group was in fine spirits.

Our Chinese guide was a little old man (perhaps sixty, though it is always hard to tell with Asians because they age so well) who spoke only one word of English: “okay”. We never caught his name; he was introduced simply as “the guide” when we picked him up on the side of the road. From now on, I’ll refer to him as Wang because he needs a name. Wang led our group in slow, measured steps up the mountainside, on a narrow, rocky trail encroached upon by thick brush from both sides. The slow but steady pace of the ascent made the otherwise rigorous terrain quite manageable, even for a little whiner like me who hates steep inclines. Wang clearly felt no sense of urgency and everyone in the group was in fine spirits.

The Forbidden City lies adjacent to Tiananmen Square. We headed toward the entrance, drawn to the colorful rooftop of the hall towering over the Meridian Gate. We rented an audio guide with a built-in GPS system and walked inside. The Imperial Palace, now know as the Forbidden City because it was off-limits for 500 years, was constructed during the Ming dynasty in the 15th century and served as a secluded palace home to two dynasties of Chinese emperors: the Ming and the Qing. The compound was designed such that the emperors rarely had to leave its decadent, insulated confines. With a 2.6 million square foot area of halls, galleries, gardens and courtyards, it is not difficult to imagine living an entire life inside the foreboding city walls. The emperors held court, gave public speeches, received felicitations on special occasions, hosted foreign dignitaries, studied, amassed a great many treasures and lived their daily lives within the city walls. The main areas of the city were its various great halls, built in perfect alignment through the center of the compound. Each hall had a specific function and was richly decorated in blue, green, red and gold. The design of the halls and their opulent adornments were intended to acknowledge the divine right of the emperor to rule the people.

The Forbidden City lies adjacent to Tiananmen Square. We headed toward the entrance, drawn to the colorful rooftop of the hall towering over the Meridian Gate. We rented an audio guide with a built-in GPS system and walked inside. The Imperial Palace, now know as the Forbidden City because it was off-limits for 500 years, was constructed during the Ming dynasty in the 15th century and served as a secluded palace home to two dynasties of Chinese emperors: the Ming and the Qing. The compound was designed such that the emperors rarely had to leave its decadent, insulated confines. With a 2.6 million square foot area of halls, galleries, gardens and courtyards, it is not difficult to imagine living an entire life inside the foreboding city walls. The emperors held court, gave public speeches, received felicitations on special occasions, hosted foreign dignitaries, studied, amassed a great many treasures and lived their daily lives within the city walls. The main areas of the city were its various great halls, built in perfect alignment through the center of the compound. Each hall had a specific function and was richly decorated in blue, green, red and gold. The design of the halls and their opulent adornments were intended to acknowledge the divine right of the emperor to rule the people. We had worked up quite an appetite and decided to walk to a narrow side street in the nearby Wangfujing district, nicknamed “Snack Street”. In reality it was more like an alleyway ornamented with a large colorful archway at the entrance. It was lined with food stalls and a few small restaurants. One vendor displayed skewers of scorpions, seahorses, snakes, starfish, and a variety of insects which could be fried upon request. I found it quite disturbing, especially the seahorses, which are so rare and beautiful. We passed on the exotic fare and were instead lured into one of the restaurants where there was no menu whatsoever and no one spoke English. We managed to order some dumplings and noodles (although we actually got noodle soup instead). We have found the food in China to be oily and mediocre so far but, after a long, hot day of walking in the Forbidden City, we were happy just to sit.

We had worked up quite an appetite and decided to walk to a narrow side street in the nearby Wangfujing district, nicknamed “Snack Street”. In reality it was more like an alleyway ornamented with a large colorful archway at the entrance. It was lined with food stalls and a few small restaurants. One vendor displayed skewers of scorpions, seahorses, snakes, starfish, and a variety of insects which could be fried upon request. I found it quite disturbing, especially the seahorses, which are so rare and beautiful. We passed on the exotic fare and were instead lured into one of the restaurants where there was no menu whatsoever and no one spoke English. We managed to order some dumplings and noodles (although we actually got noodle soup instead). We have found the food in China to be oily and mediocre so far but, after a long, hot day of walking in the Forbidden City, we were happy just to sit.