Posted under Africa & Tanzania

After three incredible nights in Paje, we decided to move to Kendwa Beach on the northern tip of Zanzibar. There are essentially three modes of transportation available for getting around on Zanzibar: private taxi (most expensive), private minibus, and daladala (dirt cheap). We had taken a taxi from Stone Town to Paje but, in the interest of curbing transportation costs and for the sheer adventure of it, we wanted to take the daladala from Paje to Kendwa, passing through Stone Town. As fate would have it, a private minibus driver at Cristal made us an offer we couldn’t refuse on a ride to Stone Town and dropped us off at the local spice market from which the daladalas departed. We paid the mzungu price of two thousand Tanzanian shillings each (still dirt cheap) for an hour long ride from Stone Town to Kendwa. We hoisted our packs onto the roof of the open-air truck bed where they were piled on top of sacks of food and construction supplies. We then climbed into the back with about fifteen locals sitting shoulder-to-shoulder on the bench seats. When the daladala was satisfactorily stuffed with patrons, a barefoot conductor hopped onto the back and signaled the driver to pull away by clanking on the metal frame of the roof structure with a stack of coins.

After three incredible nights in Paje, we decided to move to Kendwa Beach on the northern tip of Zanzibar. There are essentially three modes of transportation available for getting around on Zanzibar: private taxi (most expensive), private minibus, and daladala (dirt cheap). We had taken a taxi from Stone Town to Paje but, in the interest of curbing transportation costs and for the sheer adventure of it, we wanted to take the daladala from Paje to Kendwa, passing through Stone Town. As fate would have it, a private minibus driver at Cristal made us an offer we couldn’t refuse on a ride to Stone Town and dropped us off at the local spice market from which the daladalas departed. We paid the mzungu price of two thousand Tanzanian shillings each (still dirt cheap) for an hour long ride from Stone Town to Kendwa. We hoisted our packs onto the roof of the open-air truck bed where they were piled on top of sacks of food and construction supplies. We then climbed into the back with about fifteen locals sitting shoulder-to-shoulder on the bench seats. When the daladala was satisfactorily stuffed with patrons, a barefoot conductor hopped onto the back and signaled the driver to pull away by clanking on the metal frame of the roof structure with a stack of coins.

Despite Aaron’s suggestion otherwise, I was wearing shorts and a sleeveless shirt – I was going from one beach resort to another for goodness sake! – which drew the usual stares from the Muslim locals, though the offenders at least tried to be discreet. It is interesting how you can always feel a stare upon you, especially the penetrating eyes of disapproval or contempt, even when you purposely avoid making eye contact. I notice it to a greater degree as a minority in race and religion and as a foreigner in this conservative, tribal culture. In my opinion, we would have exacted the same stares if I’d worn a berka, just for being mzungus. In fact, we stopped briefly near a group of schoolgirls and one of them shouted, “Ay, Mzungus!”, and pointed at us as if we were monkeys in the zoo. We smiled and waved, laughing at the spectacle of giggling schoolgirls as the daladala drove away.

I had made a conscious choice of attire that morning, knowing full well that we planned to ride the daladala with the locals. There were a number of reasons for my choice. First, the Tanzanians, particularly the Zanzibaris, are nothing like the Egyptians – my fleshy exhibition was not going to put us in danger of being drawn into a street brawl. Second, though I have grown increasingly more traditional in my thirties about the domestic role that I want to play in my family dynamic, I am a bull-headed, outspoken, unapologetic American feminist on the subject of women’s rights and equality. I don’t like to be told what to wear. Aaron suggested that I was being culturally insensitive and he was probably right on many levels. While I admit that it tickles my personal fancy to stir the proverbial pot, my motivation in this scenario lay in setting a flesh and blood example of a liberated woman who can stand proudly on her own or by her loving husband’s side, wearing whatever she wants (and nothing she doesn’t), with the poise, confidence and dignity of a queen. I am not so naïve, however, as to presume that this is always how I am perceived. A woman sitting across from me on the daladala had a ten minute conversation with the young man next to her while repeatedly gesturing toward my bare legs. She spoke Kiswahili so we’ll never know what she said but her expression suggested disapproval. This sort of thing never bothers me and I responded with friendly smiles.

Between Stone Town and Kendwa, the daladala stopped periodically, letting passengers off and taking on others; all of these exchanges were orchestrated by the barefoot conductor with his clanking coins, who stood on the bumper for most of the ride because the vehicle was consistently filled beyond capacity. Aaron captured the daladala experience most accurately when he said that if the vehicle, comfortably but snugly, fits fifteen, they’ll pack in twenty and, if there are five more people along the way, they’ll squeeze them in too. It doesn’t seem to be as much about maximizing profits, however, as simply giving a ride to someone in need of one. They won’t leave a man behind in the interest of personal space for the existing passengers. There is no concept of personal space in Africa. There is always room for one more.

We stopped once for a young mother and baby alongside the road. The truck was already packed so tightly that my hips were beginning to go numb from being squeezed from both sides but the barefoot conductor nonetheless grabbed hold of the baby while the mother climbed over about twenty pairs of tangled legs to a narrow corner in the back. The big-eyed baby girl was then passed, without the slightest whine of protest, through an assembly line of arms until she landed safely on her mother’s lap. It was at once strange and beautiful.

The daladala dropped us off at a roundabout two kilometers from Kendwa. With two sets of bruised (from the hard, wooden plank seats) suburban buns, we were happy to hump the final distance down the dirt road.

We are constantly fascinated by our experiences on African public transportation.

It would be wishful thinking to suggest that we commune with the locals when we ride their uncomfortable, sweaty buses rather than travel by plane like the majority of the mzungus. The race disparity is much more pronounced here than it is in the States. In my observation, almost without exception in both Kenya and Tanzania, the white people are here either as tourists or in a business or philanthropic capacity. The locals are black tribal peoples who didn’t grow up with white people living down the street or going to the same schools. We are foreign to each other though we can speak the same language. I recently read The Poisonwood Bible, by Barbara Kingsolver, about a tyrannical Southern Baptist minister who drags his American wife and four young daughters to the Congo to impose his religious beliefs on the local tribal villagers. I see many similarities between the cultural barriers that we have experienced and those described by the wife and daughters in the book. We can sit shoulder-to-shoulder with the locals on their daladalas, shop in their markets, solicit their businesses, exchange smiles and pleasantries, but we cannot begin to penetrate the tribal barriers which have been solidified over generations. Certainly not in the two to four weeks that we have allocated to each African country on our itinerary and, in reality, probably not in a lifetime.

On countless occasions, we have driven through rural villages where the villagers chase after the bus, feverishly shoving fresh vegetables or some other local product up to the windows. On those same streets, I always see women of about my age sitting idly on the ground, leaning against a storefront or house. They all seem to have the same distant look on their faces. I search my own catalog of womanly emotions and experiences for some semblance of insight into the thoughts behind those vacant expressions and, invariably, I come up empty. These women have lived lives in a world that I cannot begin to understand from my passing bus window. I want to reach inside their souls and look at the colors, to study their faces and hear their stories, but for selfish reasons, for my own collection box of memories. This desire does not seem to be reciprocated by the people here, least of all by the women who seem to want the least to do with us. Perhaps it is a trivial and indulgent desire, afforded to a silly American woman who has never known hunger, struggle or pain in comparison. I am from a world that is unfathomable to these women, a world of luxuries and excesses that seem so vain from this dirt road in the middle of rural Tanzania.

Speaking of vain luxuries, Amaan Beach Resort in Kendwa has not disappointed! The beach is every bit as beautiful as Paje. The sand is peppered with seashells but the tide is higher so we can swim at all hours of the day. The resort atmosphere is livelier than the sleepy bungalow setting that we enjoyed in Paje but there are also more services. Our garden view room is perfect and we have reached the point of true relaxation. The grounds, particularly the lush, manicured garden courtyard, are nothing short of a spectacular botanical paradise. Because Kendwa is on the western side of the northern tip of the island, we also get brilliant sunsets over the water.

We are staying three nights here and there are no excursions tempting enough to lure us out of our zone of relaxation. Truth be told, we know that nothing can top the dolphins and we are still glowing in the aftermath. After two incredible nights, we still haven’t ventured out of the resort with the exception of a morning walk along the beach. We swim with our scuba masks during the day and have seen starfish, sea urchins, several varieties of crabs and two kinds of jellyfish, which have been kind enough not to sting us yet.

On one of our walks, we found a starfish that had washed up onto the shore but was still weakly hanging onto life. Aaron picked it up with his flip flop and gently flung it into the water. At first, it just lay on the ocean floor, upside down, too weak to turn itself over. Then, by a stroke of luck, a gentle current swept through the water, turning the starfish halfway over; slowly but surely, as we cheered from the sidelines, it began to right itself, one long leg at a time. It was our good deed for the day and we celebrated by lounging like beached whales for the next eight hours.

At sunset, the water is almost dead calm, rippling just enough to glisten in the waning sunlight. Last night, we were sitting at a table on the beach listening contentedly to the Eagles, as the big orange ball sank slowly toward the horizon. The water looked irresistibly calm and inviting so we peeled off our clothes and swam furiously toward the sun. When we reached a good distance from shore, we lay on our backs, splashing, giggling and working to stay afloat. I would have believed that time stopped for those precious few moments were it not for the natural clock on the horizon. When the sun had just sunken low enough that the sky was illuminated by a dull iridescent glow, we began swimming toward the shore in a slow elementary backstroke, which naturally evolved into a furiously competitive backstroke race to the shore.

While we could easily conceive of staying longer on Zanzibar, we both feel so completely rejuvenated that the excitement of our upcoming African destinations is beginning to pull at us with a magnetic force. Concluding a tropical beach vacation is so much more satisfying when you don’t have to return to a hundred emails and a stack of files at work. So tomorrow we’re off on the fast ferry back to Dar and, if the stars are in alignment, Zambia here we come!

We cruised a bit further from the shore until we could see several groups of them around our boat. We excitedly pulled on our snorkel gear and rolled off the sides of the boat. Almost as soon as I put my mask into the water, I saw them – sleek gray dolphins gliding through the water below us and on all sides. They were beautiful and they were everywhere! On several occasions, we would see nine or ten of them swimming about twenty feet below us while we floated above with our masks in the water. Then the dolphins would start rising toward the surface, gliding slowly and sometimes only an arms length away! They would stay with us for five to ten minutes at a time and, when the dolphins would swim away, we’d patiently wait for them to resurface, then frantically swim to catch up to them. When they were too far away, we would swim back to the boat and go looking for more. There were so many dolphins around us that we were hardly in the boat at all! No sooner would we all climb back into the boat than a new group of them would surface just a short distance away and we’d flop back into the water and kick furiously after them.

We cruised a bit further from the shore until we could see several groups of them around our boat. We excitedly pulled on our snorkel gear and rolled off the sides of the boat. Almost as soon as I put my mask into the water, I saw them – sleek gray dolphins gliding through the water below us and on all sides. They were beautiful and they were everywhere! On several occasions, we would see nine or ten of them swimming about twenty feet below us while we floated above with our masks in the water. Then the dolphins would start rising toward the surface, gliding slowly and sometimes only an arms length away! They would stay with us for five to ten minutes at a time and, when the dolphins would swim away, we’d patiently wait for them to resurface, then frantically swim to catch up to them. When they were too far away, we would swim back to the boat and go looking for more. There were so many dolphins around us that we were hardly in the boat at all! No sooner would we all climb back into the boat than a new group of them would surface just a short distance away and we’d flop back into the water and kick furiously after them. At the ferry dock in Dar es Salaam, there are several classes of ferry tickets listed on the board but foreigners may only purchase the most expensive VIP tickets at $20 each…and that’s for the slow ferry. Additionally, the Tanzanians have a currency scam going on from Arusha to Zanzibar. They quote all prices in U.S. dollars but when you actually pay in their local currency (the Tanzanian shilling), they use an outrageous conversion rate, which inevitably adds a couple of dollars to the original price. It is so infuriating, especially when they do it with a smug grin that says “yes, I know I’m screwing you but there’s nothing you can do about it”, but we’re dealing with it begrudgingly…for now anyway.

At the ferry dock in Dar es Salaam, there are several classes of ferry tickets listed on the board but foreigners may only purchase the most expensive VIP tickets at $20 each…and that’s for the slow ferry. Additionally, the Tanzanians have a currency scam going on from Arusha to Zanzibar. They quote all prices in U.S. dollars but when you actually pay in their local currency (the Tanzanian shilling), they use an outrageous conversion rate, which inevitably adds a couple of dollars to the original price. It is so infuriating, especially when they do it with a smug grin that says “yes, I know I’m screwing you but there’s nothing you can do about it”, but we’re dealing with it begrudgingly…for now anyway.

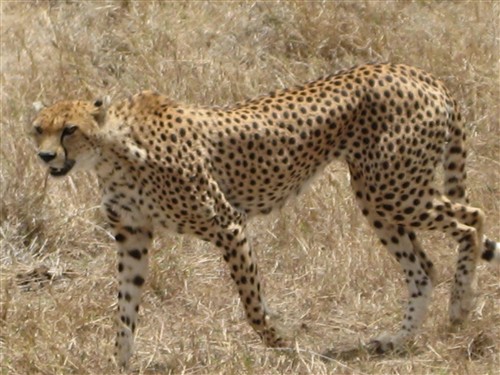

The next couple of hours were uneventful but just as we were mentally winding down for the conclusion of our safari, our guide spotted a cheetah in the distance! Through the binoculars, we could see that it was sitting erect and alert so we patiently watched it for about fifteen or twenty minutes when, suddenly, it stood up and started walking our way! We stared in wild-eyed amazement as the lanky, spotted cat – the world’s fastest animal – walked with stunning elegance right past our truck, growling and frothing at the mouth, ready to hunt. It was the only time that we had seen one of the big cats in motion and it was unquestionably the most spectacular, thrilling sight in all of our safari adventures.

The next couple of hours were uneventful but just as we were mentally winding down for the conclusion of our safari, our guide spotted a cheetah in the distance! Through the binoculars, we could see that it was sitting erect and alert so we patiently watched it for about fifteen or twenty minutes when, suddenly, it stood up and started walking our way! We stared in wild-eyed amazement as the lanky, spotted cat – the world’s fastest animal – walked with stunning elegance right past our truck, growling and frothing at the mouth, ready to hunt. It was the only time that we had seen one of the big cats in motion and it was unquestionably the most spectacular, thrilling sight in all of our safari adventures.