Posted under Morocco

A modern air-conditioned train delivered us to Fes and back into the madness of the medina. Casablanca’s gentle sea breeze was noticeably absent in the dusty desert air. The taxi dropped us off at the bustling Bab Bou Jeloud gate to the medina (because cars are not allowed inside) and we wandered into the stone labyrinth that is the Arabic old town. Our hotel was spartan but well-located and the hypnotic hum of the medina soon drew us into its chaotic colorful corridors.

We sat for an early dinner at an outdoor café near the Bab Bou Jeloud gate and finally sampled the tajine – a hot pot stew of meat and vegetables, cooked in a cone-shaped terra cotta baking dish. The meat was grisly but the vegetables were delectable and we sopped up every last drop of the rich olive oil broth as we had seen the locals do in Marrakech.

As we watched the crowds of locals and tourists shuffle through the medina, our attention was drawn to the occasional provocatively dressed European tourist – they stick out like a sore thumb among the modest jellaba-clad locals – and I was reminded of a conversation that we had had in Marrakech regarding the differences between Moroccans and Egyptians. I noted the gentle nature, the lighthearted smiles, and the seeming acceptance of Westerners by Moroccans in stark contrast to the Egyptians with their suspicious, judgmental eyes and fierce cunning. Aaron suggested that perhaps we (our perspectives, that is) are different after a year of travel, a notion I dismissed initially but now reflected upon as I studied the uncomfortable looks of the naïve young women with heaving cleavage, only vaguely aware of their effect on the ravenous, sexually repressed pack of wolves lurking in the shadows. I gazed upon the bouncing bosoms, spaghetti straps, and short skirts, asking the flesh-bearers telepathically, Look around you. Why would you wear that?

As we watched the crowds of locals and tourists shuffle through the medina, our attention was drawn to the occasional provocatively dressed European tourist – they stick out like a sore thumb among the modest jellaba-clad locals – and I was reminded of a conversation that we had had in Marrakech regarding the differences between Moroccans and Egyptians. I noted the gentle nature, the lighthearted smiles, and the seeming acceptance of Westerners by Moroccans in stark contrast to the Egyptians with their suspicious, judgmental eyes and fierce cunning. Aaron suggested that perhaps we (our perspectives, that is) are different after a year of travel, a notion I dismissed initially but now reflected upon as I studied the uncomfortable looks of the naïve young women with heaving cleavage, only vaguely aware of their effect on the ravenous, sexually repressed pack of wolves lurking in the shadows. I gazed upon the bouncing bosoms, spaghetti straps, and short skirts, asking the flesh-bearers telepathically, Look around you. Why would you wear that?

And then I remembered a walk that I once took in some nameless village along the Nile where the two strong men at my side were powerless to stop the scornful, penetrating stares of the Egyptian villagers or the rocks thrown by a gang of brainwashed young boys. The shock, confusion and intimidation of that experience preceded our understanding of Arab-Islamic culture. At the time, I was adamantly opposed to succumbing to the oppression of women that I so despised, and offended by the notion that I should conform or be treated like a whore on the street, but such is the way of life for women in Arab cultures. The women cover themselves completely, even on the hottest days of the desert summer because the men are like animals, like dogs in heat with uncontrollable animalistic behavior incited by the smallest visible sliver of feminine flesh. In this culture, the abhorrent behavior of men goes socially and legally unchecked – women are hissed at, cat-called, groped in crowds – and there is no recourse. Women are still second class citizens – equal rights are yet a distant dream. The people are raised from childhood to believe that immodest dress makes a woman undeserving of respect. Such is life in Morocco. But understanding this crude, archaic social more makes walking the streets of Morocco a different experience. My spaghetti straps have long since been retired and, in crowds, I attach myself to Aaron’s hip because a woman walking alone in a crowd is a target for anonymous gropers. In the thickest crowds, I walk with my arms crossed over my chest to avoid any “accidental” contact. When we walk through the medina, entranced by the sights, sounds and smells, I can easily tell when Aaron has fallen behind by the hawkish muted advances of the all-male shopowners.

I find this aspect of Arab-Islamic culture vile and reprehensible. But where once I (clad in spaghetti straps) vowed to take on the beast of oppression singlehandedly by setting an example of an independent woman who is treated as her husband’s equal, I now realize that education and economic prosperity are better swords to wield in that battle than my insolent bare shoulders. While I stand by my original generalization that Moroccans are gentler and more tolerant of Westerners than the Egyptians, I also see that our perspective is different, worldly, more educated. Understanding breeds tolerance.

By the time we arrived in Fes, the atmosphere of the medina, with its mosques and medersas, had lost a bit of its luster. While we engaged in the requisite aimless wandering, we found ourselves seeking quiet refuge from the hustle and intensity of the streets. When you have the sponge-like desire for the sensory overload of Third World culture, the Moroccan medina delivers an explosion of colorful produce stalls, freshly butchered carcasses hanging in shop fronts, enchanting Arabic music, donkey carts, street hustlers, savvy rug dealers, burqa-clad women peering out through their narrow eye-slits, the constant engagement of shopowners beckoning you inside for a look, dark clandestine corners, aromas of fresh mint and cilantro filling the air…all in a buzzing kaleidoscope of stimulation. Even the sidewalk cafés are fair game for amateur tour guides, beggars and street performers. When you are weary of the chaos, you must find oases on elevated terraces, in high-end hotels and quiet internet cafés.

By the time we arrived in Fes, the atmosphere of the medina, with its mosques and medersas, had lost a bit of its luster. While we engaged in the requisite aimless wandering, we found ourselves seeking quiet refuge from the hustle and intensity of the streets. When you have the sponge-like desire for the sensory overload of Third World culture, the Moroccan medina delivers an explosion of colorful produce stalls, freshly butchered carcasses hanging in shop fronts, enchanting Arabic music, donkey carts, street hustlers, savvy rug dealers, burqa-clad women peering out through their narrow eye-slits, the constant engagement of shopowners beckoning you inside for a look, dark clandestine corners, aromas of fresh mint and cilantro filling the air…all in a buzzing kaleidoscope of stimulation. Even the sidewalk cafés are fair game for amateur tour guides, beggars and street performers. When you are weary of the chaos, you must find oases on elevated terraces, in high-end hotels and quiet internet cafés.

In the medina, daily life is dictated by two things: religion and the sweltering heat. The notion of “nine-to-five” has no place here. The morning begins around 5 am with the muezzin’s resonating call to prayer. Laborious tasks begin early before the oppressive heat makes them unbearable. Shopowners begin the daily ritual of setting out their displays while restaurant owners make the day’s purchases from produce sellers. Men huddle around outdoor tables, drinking green tea with springs of fresh mint. In the sizzling afternoons, they can be found snoozing away in shady places. From dusk until dawn, the streets of the medina are most alive with bright lights, music and non-alcoholic revelry. Small children roam the streets at all hours of night, an initially shocking sight that quickly melts into normalcy. The street noise jolted us from sleep at all hours of the night until the muezzin’s call signaled the break of day and a new cycle of working, socializing, napping. Such is life in the medina. It is a different world, a world from which we are now eagerly anticipating our escape.

Morocco has been a sideshow on our European home stretch. The truth is that we are weary of the Third World, weary of the emotional albatross that is poverty, weary of the discomforts and the hustle. Morocco is interesting because it seems more like the Middle East than Africa. The people have a stunning golden complexion, similar to Iranians, and their language, style of dress, cuisine and mannerisms are characteristic of Arabs. But often enough, a “T.I.A.” moment reminds you of what continent you’re on.

My praise of the Moroccan train system was perhaps a bit premature, as evidenced by our final train ride from Fes to Tangier. Tickets were sold for an air-conditioned ride but the vents inside the cars blew only a whisper of cool air. If you held your arm three or more inches above the vent, you could not feel the air at all. In the blazing mid-afternoon heat, the train filled to capacity at the main junction near Sidi Kacem and sat there delayed for almost two hours while the passengers perspired together in the uncirculated hot boxes. Also at that junction, the train was oversold and many unfortunate passengers, including mothers with small children, were forced to sit on the floor between cars. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, I’ll just mention that the restrooms were utterly vile without going into my usual level of grotesque detail. T.I.A. This is Africa.

The locals all seemed to bear the discomfort and inconvenience with grace, as if this level of service was standard or perhaps because they understand an important truth: there are many worse things to bear in life than a little physical discomfort and inconvenience. Sometimes a petty difficulty, when put into perspective, can be a healthy reminder of the many blessings in our lives.

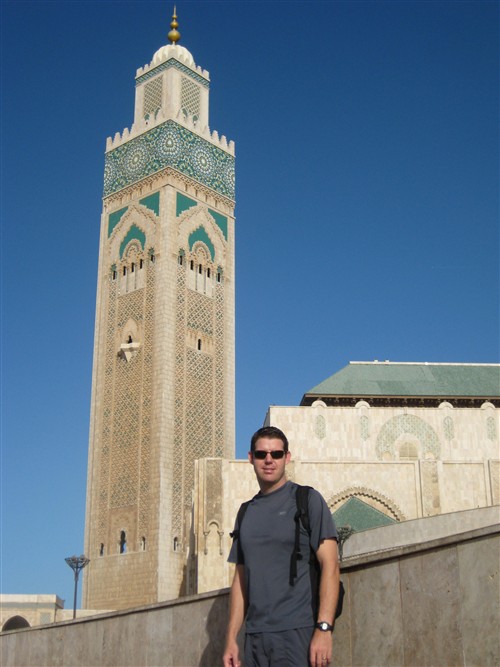

The real Casablanca is nothing like the movie. The movie wasn’t even filmed there, in fact; it was filmed in Hollywood and based on a hotel in Tangier. Casablanca is Morocco’s most cosmopolitan and industrial city. A taxi driver proudly informed us, “Casablanca is not for tourists. Casablanca is for business.” We arrived by train from Marrakech, a comfortable three-hour ride through the desolate Sahara Desert; and, upon reading that Casablanca’s restaurants serve up excellent seafood, we splurged on fruits des mer and another impressive bottle of Moroccan red wine at a French Provencal place near our hotel.

The real Casablanca is nothing like the movie. The movie wasn’t even filmed there, in fact; it was filmed in Hollywood and based on a hotel in Tangier. Casablanca is Morocco’s most cosmopolitan and industrial city. A taxi driver proudly informed us, “Casablanca is not for tourists. Casablanca is for business.” We arrived by train from Marrakech, a comfortable three-hour ride through the desolate Sahara Desert; and, upon reading that Casablanca’s restaurants serve up excellent seafood, we splurged on fruits des mer and another impressive bottle of Moroccan red wine at a French Provencal place near our hotel.

Away from the food stalls, the remaining area of the square is utterly consumed by the equivalent chaos of ten circuses operating simultaneously in the dark with crowds of spectators gathered around each one. The performers – all men – make music and dance, perform plays and acrobatics. Within a twenty foot radius, you can get henna-painted hands and feet, watch snake charmers, get a custom-mixed herbal remedy for whatever is ailing you, and pose for photos with a monkey on your head. The days are so oppressively hot that seemingly everyone comes out a night – old women, families pushing strollers, and young boys – to witness the grand festivities. The air is bursting with music, laughter and energy. Your heart begins to race along with the tempo of the drums. It is madness!

Away from the food stalls, the remaining area of the square is utterly consumed by the equivalent chaos of ten circuses operating simultaneously in the dark with crowds of spectators gathered around each one. The performers – all men – make music and dance, perform plays and acrobatics. Within a twenty foot radius, you can get henna-painted hands and feet, watch snake charmers, get a custom-mixed herbal remedy for whatever is ailing you, and pose for photos with a monkey on your head. The days are so oppressively hot that seemingly everyone comes out a night – old women, families pushing strollers, and young boys – to witness the grand festivities. The air is bursting with music, laughter and energy. Your heart begins to race along with the tempo of the drums. It is madness!

By our third night in Marrakech, we had the medina and the main square pretty well figured out. We took in a few more sights around the kasbah and regrouped at the riad. We were joined by the young Brits whom I mentioned earlier and Juan who had returned from a camel safari in the outlying desert. Janice, our lovely hostess, had generously sent down a couple half-bottles of surprisingly delicious Moroccan wine which warmed our spirits for our final night out in the Djemaa el-Fna. Wandering through the intense revelry, I strained to memorize every sight, sound and smell. Clouds of smoke from the grills billowed through the night air, blurring the bright lights, burning my eyes, filling my nose with tantalizing aromas. The beating of the drums folded into one unified rhythm. It felt like a wild dream.

By our third night in Marrakech, we had the medina and the main square pretty well figured out. We took in a few more sights around the kasbah and regrouped at the riad. We were joined by the young Brits whom I mentioned earlier and Juan who had returned from a camel safari in the outlying desert. Janice, our lovely hostess, had generously sent down a couple half-bottles of surprisingly delicious Moroccan wine which warmed our spirits for our final night out in the Djemaa el-Fna. Wandering through the intense revelry, I strained to memorize every sight, sound and smell. Clouds of smoke from the grills billowed through the night air, blurring the bright lights, burning my eyes, filling my nose with tantalizing aromas. The beating of the drums folded into one unified rhythm. It felt like a wild dream.