Posted under Nepal

This post contains a reference to recent medical problems with our pregnancy while traveling through China and Nepal. We originally omitted the stories so as not to worry our friends and family but since the pregnancy has come to an end we have decided to share the details of our saga. We have added some additional posts and have pre-dated them to appear in chronological order. To follow the story from the beginning, start with “The Grand Finale” and the story of our visit to a Chinese emergency room.

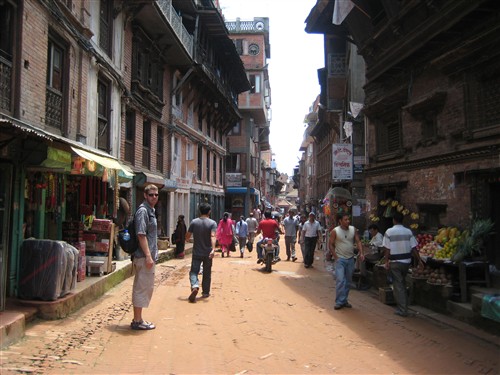

We returned to Kathmandu on an air-conditioned minibus, still anxious to leave Nepal. Due to our medical issue, we’ve been confined to Nepal’s two major cities and their nearby medical facilities, exacerbating our anxiety. This precluded us from trekking in the Himalayans or going on safari in Chitwan National Park to stalk Bengal tigers, but it was our reality. After the relative peace of Pokhara, Kathmandu was like a splash of cold water on our faces. The incessant honking horns and chaotic, traffic-filled streets made us reluctant to leave the serenity of our room at the Tibet Guest House. On the occasions when we did venture out, there were shopkeepers who expectantly greeted us as we passed their stores, hoping we’d stop to look at their tired wares. And there were beggars and rickshaw touts and trekking guides and a laundry list of others eager to separate us from our remaining rupees. After spending five of the last seven months in Asia, the majority of time in poverty-stricken developing countries, our patience and tolerance has worn thin. It’s unfortunate that our “Asia fatigue” has so negatively colored our last month of travel through China and Nepal. We’ve both agreed that had we visited Nepal or China as “two-weekers”, or without the anxiety of managing an impending miscarriage in a Third World country, our perspectives might have been different. C’est la vie. So with the exception of a quick day trip to the ancient city of Bhaktapur – the oldest and most pedestrian-friendly of the three cities in the Kathmandu valley – we hid out in our room, forced to bide our time until our flight to Paris.

We returned to Kathmandu on an air-conditioned minibus, still anxious to leave Nepal. Due to our medical issue, we’ve been confined to Nepal’s two major cities and their nearby medical facilities, exacerbating our anxiety. This precluded us from trekking in the Himalayans or going on safari in Chitwan National Park to stalk Bengal tigers, but it was our reality. After the relative peace of Pokhara, Kathmandu was like a splash of cold water on our faces. The incessant honking horns and chaotic, traffic-filled streets made us reluctant to leave the serenity of our room at the Tibet Guest House. On the occasions when we did venture out, there were shopkeepers who expectantly greeted us as we passed their stores, hoping we’d stop to look at their tired wares. And there were beggars and rickshaw touts and trekking guides and a laundry list of others eager to separate us from our remaining rupees. After spending five of the last seven months in Asia, the majority of time in poverty-stricken developing countries, our patience and tolerance has worn thin. It’s unfortunate that our “Asia fatigue” has so negatively colored our last month of travel through China and Nepal. We’ve both agreed that had we visited Nepal or China as “two-weekers”, or without the anxiety of managing an impending miscarriage in a Third World country, our perspectives might have been different. C’est la vie. So with the exception of a quick day trip to the ancient city of Bhaktapur – the oldest and most pedestrian-friendly of the three cities in the Kathmandu valley – we hid out in our room, forced to bide our time until our flight to Paris.

But our time in places like Nepal has given us a different perspective on world affairs. Like everyone else in the world, we’ve been anxiously following the subprime mortgage debacle and the US economy spiraling downward into a recession; banks are defaulting on loans and deposits and gas prices have soared to record highs. We certainly aren’t immune to these affects even as we travel; the exchange rates of the US dollar to many major currencies are at all time lows, the interest accrued on our ever-shrinking pot of travel money has slowed to a trickle, and the cost of petrol has made every mode of transportation more expensive. We are, in fact, planning to return to the US by the end of the year, shortening our intended itinerary, because we’re over budget, though it is as much attributed to our own decadence as to the fuel prices or dollar’s decline. But let me paint a picture for you of how the fuel crisis is affecting Nepal, this tiny country on the other side of the world.

The increasing global oil prices have created a nightmare for one of the world’s poorest nations. The Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC) is a state-run company and the sole supplier of petrol products for the country, sourcing the majority, if not all of their oil through contractual agreements with India. But with rapidly rising oil prices, the cash-strapped corporation has been unable to continue purchasing petrol from their Indian partners. The result of this price increase is unbelievable. Petrol stations in Nepal are closed during the day, opening only in the evening; and that’s only if the daily petrol truck arrives. Lines begin forming early in the afternoon and swell throughout the evening, lining city streets and congesting the already narrow roadways. Drivers wait in lines stretching more than a mile long, often waiting five or more hours for their turn at the pump. Traffic slows to a crawl on the crowded streets. The lines are guarded and traffic is tightly controlled by the Nepalese Army – tensions are high.

If a driver actually reaches the pump and petrol is available, it costs the equivalent of $9 per gallon – double what it costs in the US – with the price increasing each week. And that’s if it’s even available! Our last week in Nepal, the NOC announced that they no longer had enough cash to continue purchasing petrol and they were trying to secure interim financing just to continue operations. As a result, less than one-third of Kathmandu’s normal petrol needs were being met, crippling Nepal’s infrastructure. For a nation already dependent on handouts from the world to keep it functioning from one day to the next, the immediate future doesn’t look very bright.

Tina wasn’t interested in anything involving camping but I was eager for another outing, so I ventured out alone on an overnight rafting trip. One of the local rafting shops, Paddle Nepal, put together a two-river, one night camping package; a surprising feat in the off-season. With our experiences on the Zambezi setting the standard, I was keeping my expectations low. Our party consisted of one guide, three safety kayakers, and six rafters: four twenty-something British girls – volunteer teachers at local schools – and a young professional woman from San Francisco on holiday.

Tina wasn’t interested in anything involving camping but I was eager for another outing, so I ventured out alone on an overnight rafting trip. One of the local rafting shops, Paddle Nepal, put together a two-river, one night camping package; a surprising feat in the off-season. With our experiences on the Zambezi setting the standard, I was keeping my expectations low. Our party consisted of one guide, three safety kayakers, and six rafters: four twenty-something British girls – volunteer teachers at local schools – and a young professional woman from San Francisco on holiday. The next morning we were surprised to learn that we would be taking local buses instead of chartered transport. It wasn’t a big deal but I soon realized that it was going to be a lot longer day than I had anticipated. We hailed down a nearly full local bus heading upriver, and after loading all our gear onto the roof, we were off toward our drop point on the Trisuli. By the time we reached our stop and descended to the river’s edge, the rain was pouring down, really pouring, like where’s-Noah-with-the-Ark pouring. The Trisuli River was significantly colder than the Seti and with no sun, torrential rain, and violent rapids; I was chilled for the entire ride. The trip downriver was fun but underwhelming as our guide steered clear of the more menacing and fun-looking rapids. Our short two-hour ride was over as quickly as it had begun.

The next morning we were surprised to learn that we would be taking local buses instead of chartered transport. It wasn’t a big deal but I soon realized that it was going to be a lot longer day than I had anticipated. We hailed down a nearly full local bus heading upriver, and after loading all our gear onto the roof, we were off toward our drop point on the Trisuli. By the time we reached our stop and descended to the river’s edge, the rain was pouring down, really pouring, like where’s-Noah-with-the-Ark pouring. The Trisuli River was significantly colder than the Seti and with no sun, torrential rain, and violent rapids; I was chilled for the entire ride. The trip downriver was fun but underwhelming as our guide steered clear of the more menacing and fun-looking rapids. Our short two-hour ride was over as quickly as it had begun.

I was in the frame of mind to lay low in Pokhara and do everything possible to stay relaxed and prevent any further emergency room visits. As Aaron was feeling physically fine and needed some good distractions, we signed him up for a few adventure activities, the first of which was paragliding. I rode along for that one (in the truck, not the chute) and watched him leap from the top of the mountain and glide through the air over the breathtaking Pokhara Valley. I knew he was okay shortly after take off when I heard an ecstatic “Woohoo!” echo through the valley to which I replied, “You’re flyiiiiiing!” I excitedly snapped a dozen pictures of my falcon-like husband. As the driver and I made our way back down the mountain, we stopped to pick up an amazing sixteen locals, mostly women and children, to carry them down to town. I saw one woman pass him a bill but most paid nothing. There is just an unwritten rule that, if you have an empty truck and people need a ride, you stop for them. Though the extra stops prevented me from reaching the landing point in time for the landing, I was very moved by this beautiful yet commonplace Third World gesture.

I was in the frame of mind to lay low in Pokhara and do everything possible to stay relaxed and prevent any further emergency room visits. As Aaron was feeling physically fine and needed some good distractions, we signed him up for a few adventure activities, the first of which was paragliding. I rode along for that one (in the truck, not the chute) and watched him leap from the top of the mountain and glide through the air over the breathtaking Pokhara Valley. I knew he was okay shortly after take off when I heard an ecstatic “Woohoo!” echo through the valley to which I replied, “You’re flyiiiiiing!” I excitedly snapped a dozen pictures of my falcon-like husband. As the driver and I made our way back down the mountain, we stopped to pick up an amazing sixteen locals, mostly women and children, to carry them down to town. I saw one woman pass him a bill but most paid nothing. There is just an unwritten rule that, if you have an empty truck and people need a ride, you stop for them. Though the extra stops prevented me from reaching the landing point in time for the landing, I was very moved by this beautiful yet commonplace Third World gesture.

Next, we visited Durbar Square in the older part of town. Once the site of royal coronations, the square has more temples and shrines per square meter than anywhere we’ve been. Most of the buildings date back to the 17th and 18th centuries and little has been done to preserve or restore them. What I found most interesting about the religious structures in Durbar Square was how casually they were treated. People climbed all over them, lazing the day away on the upper levels and watching the world go by.

Next, we visited Durbar Square in the older part of town. Once the site of royal coronations, the square has more temples and shrines per square meter than anywhere we’ve been. Most of the buildings date back to the 17th and 18th centuries and little has been done to preserve or restore them. What I found most interesting about the religious structures in Durbar Square was how casually they were treated. People climbed all over them, lazing the day away on the upper levels and watching the world go by.