Posted under India

As I close my eyes and try to summarize my thoughts, a tidal wave of vibrant, fiery images floods my mind. Indian culture is so intense that I think the constant sensory overload makes Westerners – unaccustomed to such constant stimulation, lack of privacy and lack of personal space – physically ill after a while. It happened to me. After a solid month of rat-and-cockroach-infested overnight trains, squat toilets, fifth floor hostel rooms and restaurants without elevators, astonishing poverty, dizzying markets and endless haggling, my immune system simply shut down, leaving me with a self-diagnosed kidney infection (I’ve had at least six of these so I know the symptoms well), a torturous head cold, and some kind of reddening irritation in my right eye which prevented me from wearing my contact lens for a week. Our furious pace kept my adrenaline surging hard enough to delay the symptoms from emerging until we finally came to relax in Rishikesh, where I began to feel like I’d been hit by a bus. In keeping my hypothesis objective, I must confess that, out of sheer laziness, I brushed my teeth using tap water rather than bottled water for about a week, which likely contributed to my smorgasbord of ailments in addition to a host of others whose symptoms have yet to manifest. If the tap water, which likely pumped straight from the Ganges to my toothbrush didn’t kill the germophobe in me, then the squat toilets surely did because I’m feeling rather granola these days. Going number two on a sand dune tends to do that to a person; while I didn’t enjoy that experience, I also cannot deny that it was liberating. Much like Africa, India is devoid of toilet paper except in high-end hotels. Merchants sell it street side to tourists because budget hotels and most restaurant restrooms only provide that handy little water spout (and no soap!) next to the toilet instead of paper. It seems that paper products in general, including paper towels and napkins, are a luxury of the First World, one which we no longer take for granted.

As I close my eyes and try to summarize my thoughts, a tidal wave of vibrant, fiery images floods my mind. Indian culture is so intense that I think the constant sensory overload makes Westerners – unaccustomed to such constant stimulation, lack of privacy and lack of personal space – physically ill after a while. It happened to me. After a solid month of rat-and-cockroach-infested overnight trains, squat toilets, fifth floor hostel rooms and restaurants without elevators, astonishing poverty, dizzying markets and endless haggling, my immune system simply shut down, leaving me with a self-diagnosed kidney infection (I’ve had at least six of these so I know the symptoms well), a torturous head cold, and some kind of reddening irritation in my right eye which prevented me from wearing my contact lens for a week. Our furious pace kept my adrenaline surging hard enough to delay the symptoms from emerging until we finally came to relax in Rishikesh, where I began to feel like I’d been hit by a bus. In keeping my hypothesis objective, I must confess that, out of sheer laziness, I brushed my teeth using tap water rather than bottled water for about a week, which likely contributed to my smorgasbord of ailments in addition to a host of others whose symptoms have yet to manifest. If the tap water, which likely pumped straight from the Ganges to my toothbrush didn’t kill the germophobe in me, then the squat toilets surely did because I’m feeling rather granola these days. Going number two on a sand dune tends to do that to a person; while I didn’t enjoy that experience, I also cannot deny that it was liberating. Much like Africa, India is devoid of toilet paper except in high-end hotels. Merchants sell it street side to tourists because budget hotels and most restaurant restrooms only provide that handy little water spout (and no soap!) next to the toilet instead of paper. It seems that paper products in general, including paper towels and napkins, are a luxury of the First World, one which we no longer take for granted.

The most shocking sights and my most enduring memories of India are of the stark poverty, the unashamed beggars, the physical deformities, the indescribable filth and public urination that permeate every street. There are so many people sleeping on the streets. Our hearts break for them, especially the children who are sent by their parents to beg on the streets – childhood stolen before it begins. Poverty in India is widespread but Indians (except for the beggars) seem determined to work. Industry and commerce bring the streets to life and they are full of activity, lined with colorful shops and congested with incessantly honking traffic. The smells are of street food, incense, exhaust fumes and stale urine.

It took us about a month but we finally got used to living in such close proximity to animals. Mischievous monkeys are a nuisance – I was always a little afraid of them, especially when a trio of them cornered us at the breakfast table in Varanasi. They would have attacked were it not for the hotel proprietor and his slingshot coming to our rescue. Also, they eat kittens. I’ve decided that I really don’t like monkeys at all. But my heart breaks for the canines. Dogs roam freely and breed freely; every adult female dog appears to be either pregnant or nursing. There are adorable, mangy puppies everywhere and you want to cuddle them all but they’re too filthy to touch. The dogs have their own hierarchy and keep each other in line. Sadly, you also see dogs with horrible afflictions and skin diseases; some look only a day away from death by starvation. India is in desperate need of animal control. I dream of starting an organization that scoops up all of the sweet little pups and places them in loving homes where they will get plenty of food, vaccines and belly scratches, play fetch in parks and wear sweaters.

Revered by Hindus, cows rule the streets. The beloved bovines roam freely on roads, alleyways, bridges, ghats and even wander into buildings when no one is watching. They graze on trash piles and lie down for a nap in the middle of the road if the mood strikes them. Only in India can a cow live a peaceful life with no worry of becoming a steak. In India, the cows don’t moo. They say, “Life is gooooooooood.” There also seems to be a market for cow shit because women collect the patties with their bare hands and heap them onto large trays, which they carry on their heads. Many buildings are plastered with the patties like wall paper. We never did figure that one out.

The Hindu religion is vividly displayed and ingrained in Indian culture. Small, colorful shrines with statues or paintings of cartoon-like idols, burning incense sticks and fresh flowers can be spotted in every direction. The Hindus seem peaceful and accepting of other religions. They are open about their beliefs and are eager to speak about them with pride.

On one of our overnight train rides, we shared a cabin with some very nice Indian people – a man and a woman. Indians are inquisitive by nature and despite my desire to anti-socially bury my head in my book, I found myself engaged in conversation and answering the usual barrage of questions: “Where from? America? Nice country. How long in India? You like? Where have you been? How many days more in India? Only one month in India? Not enough! What you do in America?” It is common for Indians to ask how much money you make and tell you how much they make. This makes Americans uncomfortable but sometimes we say that we’re employed and divulge our former salaries because it’s easier than explaining to Indians that we quit our jobs and sold our house to travel around the world. They simply cannot fathom such a thing.

As we were more or less trapped together for what seemed like an eternity, the conversation blossomed into a discussion of diet and health, religion, marriage and family. I learned that most marriages in India are arranged by the parents. The woman spoke proudly of her three sons, for one of whom she had already secured a wife and another for whom she was in pursuit. When I asked how parents go about finding suitable wives for their sons, she said she puts the word out in the community that she has a son who is eligible for marriage. She then conducts interviews of the potential candidates. She scrutinizes the level of education, familial caste, countenance, skin tone (Indians are obsessed with this – skin whitening cream is sold in EVERY pharmacy and herbal medicine shop), facial bone structure and astrological sign of each candidate to determine if she would make a good match. She then introduces the lucky winner to her son for final approval. Not surprisingly, the woman has a wonderful relationship with her first daughter-in-law.

Interestingly, we had seen classified ads in an Indian newspaper – want ads for eligible spouses. The details given included caste, education, skin tone and age, among other features. When we later reached Varanasi, we saw a sign advertising a marriage arranger among the many vendor stalls. In India, a wedding is a marriage of families. While the age-old custom of dowry is technically outlawed, it is still widely practiced. One of the most intense curses to inflict upon an Indian man is, “May you have ten daughters and may they all marry well!”

Divorce is almost non-existent in India and is socially condemned. Both the Indian man and woman were appalled to the point of speechlessness when I told them that the American divorce rate is somewhere around fifty percent. When they finally spoke again, after about five minutes of uncomfortable silence, it was to ask whether I approved of this divorce phenomenon in America. They could not fathom that fact that almost no marriages are arranged in America. I had mentioned earlier in the conversation that I have two younger unmarried sisters. I had explained that, in my country, people meet, fall in love, and decide to marry of their own free will. Twenty minutes after the topic had expired, the woman asked again for clarification, “So if your sisters don’t find a husband, still your parents would not arrange marriage for them?” She simply could not get her mind around the concept that two mature adults could meet and make such a decision without the help of their parents. “No”, I replied, “they would NEVER arrange a marriage, not under any circumstances.” By the time we reached Varanasi, we had established that divorce is very bad and arranged marriages are fine as long as no one is forced into a bad situation against his or her will. They weren’t very convincing on that last part, however. I’m sure that the divorce discussion reaffirmed in their minds the superiority of their custom. Less than two generations ago, marriages were arranged for girls of disturbingly innocent ages. Thankfully, current law establishes the minimum age for marriage as 18 years.

With my Western mind that unapologetically cherishes and defends my Western liberties, I cannot make an argument against the Hindu custom of arranged marriages. I have too much admiration for the strong family ties, devout spirituality, and overall contentedness of the Indian people. While I believe that most adults are capable of choosing a proper partner for themselves, I can’t deny that love is blind, as the saying goes. There’s nothing like a few years of marriage to expose all of the warts and blemishes. If we marry for love, perhaps we find it easier to justify divorce if and when we decide that we no longer feel that love. At the same time, there is no love as pure, selfless, and enduring as a parent’s love for a child. This realization becomes increasingly clear with age. I would trust my parents to find me a husband just as surely as I know that I could never marry someone they disapproved of. My mother has an eerie sixth sense about people, accuracy in her initial perceptions of people, and a lack of inhibition in expressing those perceptions that drove my sisters and me crazy for years. I know that she would have conducted the search for the fathers of her grandchildren with a very critical eye. That said, I think she would agree that she could not have found a better husband for me than the one I found for myself. With each passing day, I believe more fervently that God created Aaron to be my husband. It took me a long time to find him but then, one day, there he was, doing that half stand-up thing as I approached the dinner table at the J-Bar in Tucson…my Bear. I’ve been flying ever since.

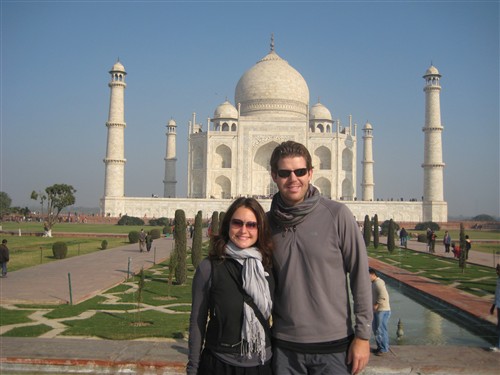

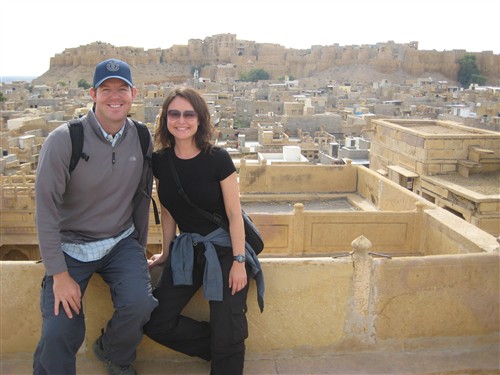

India is a treasure trove of vibrant, mysterious, colorful culture. We had prepared ourselves mentally for intense Third World discomforts and, while the cow shit, air pollution, public urination and squat toilets made those expectations a reality; we were pleasantly surprised by how much we loved it – warts, blemishes and all! We fell in love with the kind, humble, inquisitive, pleasing nature of the Indian people. They shared their food, their music and their religion with heartwarming openness. People on the street bent over backwards to help us without expecting anything in return. The cuisine was richly and deliciously inspired. It is probably best that we are no longer within easy reach of paneer butter masala and makhania lassi. Rajasthan was a jewel – we cannot recommend it highly enough as a travel destination! India is a spectacle not to be missed. We feel wiser somehow for having experienced it. India penetrates you, wraps its arms around you, and draws you into its heart. It becomes a part of you and vice versa. India is like a hideous relative with abhorrent personal hygiene who always greets you with a childish grin and a big hug and who you can’t help but love. There is no place like it in the world.

The ghats were full of activity and, although we were tired from our long journey and subsequent stress, our curiosity got the better of us and we went out for a stroll. Walking north from the Meer Ghat, where our hotel was located, we almost startlingly stumbled onto the most esteemed cremation ghat, called Manikarnika Ghat. We approached carefully, uncertain of the protocol for spectators and of our initial reaction to the sight of a burning corpse. Visitors are welcome to witness the ritual cremations but photography is strictly prohibited. The scene is vivid in my memory…

The ghats were full of activity and, although we were tired from our long journey and subsequent stress, our curiosity got the better of us and we went out for a stroll. Walking north from the Meer Ghat, where our hotel was located, we almost startlingly stumbled onto the most esteemed cremation ghat, called Manikarnika Ghat. We approached carefully, uncertain of the protocol for spectators and of our initial reaction to the sight of a burning corpse. Visitors are welcome to witness the ritual cremations but photography is strictly prohibited. The scene is vivid in my memory…

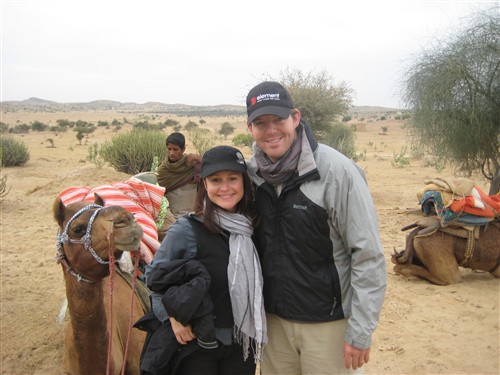

Our caravan consisted of Matthew, Carla, four South Korean students and a band of guides who expertly attended to every detail of our comfort. The day began with two hours of slow camel trekking through the Great Thar Desert. The terrain was brushy with hearty breeds of goats and sheep grazing on prickly cactus arms. Only about ten minutes into our two-hour morning stretch, we stopped outside a village of small, decrepit dwellings. The guide described it as a village of Untouchables. India has lived by the caste system of determining social status for generations. The Hindus believe that people are born into one of several castes which broadly equate to priests, nobles and commoners. A person cannot change castes in a human lifetime but living a moral life increases his chances of being born into a higher caste in the next life. Caste determines such things as the type of jobs one can hold, level of education, and marriage prospects. Untouchables are considered to be below the lowest caste.

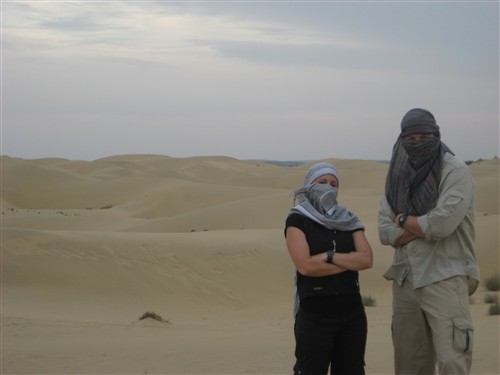

Our caravan consisted of Matthew, Carla, four South Korean students and a band of guides who expertly attended to every detail of our comfort. The day began with two hours of slow camel trekking through the Great Thar Desert. The terrain was brushy with hearty breeds of goats and sheep grazing on prickly cactus arms. Only about ten minutes into our two-hour morning stretch, we stopped outside a village of small, decrepit dwellings. The guide described it as a village of Untouchables. India has lived by the caste system of determining social status for generations. The Hindus believe that people are born into one of several castes which broadly equate to priests, nobles and commoners. A person cannot change castes in a human lifetime but living a moral life increases his chances of being born into a higher caste in the next life. Caste determines such things as the type of jobs one can hold, level of education, and marriage prospects. Untouchables are considered to be below the lowest caste. After the break, we mounted our camels once again and continued our journey to the campsite with the guides walking cheerily alongside the camel caravan. The campsite was on the edge of barren, rolling sand dunes and, as the guides set up camp, we raced up the dunes like child explorers. We jumped around, took silly pictures, made sand angels and a rather unsuccessful attempt at dune surfing, which, incidentally, doesn’t work well without a surfboard.

After the break, we mounted our camels once again and continued our journey to the campsite with the guides walking cheerily alongside the camel caravan. The campsite was on the edge of barren, rolling sand dunes and, as the guides set up camp, we raced up the dunes like child explorers. We jumped around, took silly pictures, made sand angels and a rather unsuccessful attempt at dune surfing, which, incidentally, doesn’t work well without a surfboard.